Disarmament and non-proliferation are two sides of the same coin. Progress in one spurs progress in the other.

Developments and trends, 2024

Following the pattern of recent years, 2024 continued to see acutely elevated nuclear risk, with geopolitical tensions further dividing States, and progress on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation appearing ever more elusive. References in international discourse to a “nuclear tipping point” captured an atmosphere of mounting distrust, with prior commitments going unfulfilled or facing further backsliding.

In one positive development, Member States formally recommitted in the Pact for the Future (General Assembly resolution 79/1) to “the goal of the total elimination of nuclear weapons”, demonstrating that the vast majority of the international community still held that aspiration as its guiding vision.

However, the Pact stood as one of the few bright spots in this field. The ongoing war in Ukraine continued to be characterized by nuclear rhetoric and threats. In an apparent response to increased support to Ukraine by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin signed a new nuclear doctrine in November entitled “Fundamentals of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence”. The doctrine signalled that increased NATO State engagement, especially through troop presence, or support for an attack on Russian territory by a non-nuclear-weapon State could trigger a nuclear response. Notably, the doctrine’s section on “principles of nuclear deterrence” excluded a previous provision on “compliance with international obligations in the field of arms control”.

As a direct result of the ongoing war, the P5 Process, intended to bring the five nuclear-weapon States together to discuss their unique responsibilities, did not hold any ministerial-level meetings in 2024. While working-level meetings chaired by the Russian Federation did take place, they produced no concrete outcomes.

The invasion of Ukraine continued to raise concerns about the safety and security of nuclear power plants in armed conflict, particularly the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant, where the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) continued to maintain its presence established in September 2022.

As relationships between nuclear-weapon States deteriorated, fears grew about a return to dangerous cold war practices. Former and current officials in those States issued pronouncements on the need to resume nuclear testing, and the ongoing qualitative nuclear arms race threatened to become quantitative for the first time since the 1980s. The lack of measures to prevent nuclear-weapon use, combined with the erosion of the nuclear arms control regime, stoked fears about accidental use, miscalculation and escalation. Speaking on the 2024 International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons (26 September), the Secretary-General warned that “instead of dialogue and diplomacy being deployed to end the nuclear threat, another nuclear arms race is taking shape, and sabre-rattling is re-emerging as a tactic of coercion”.

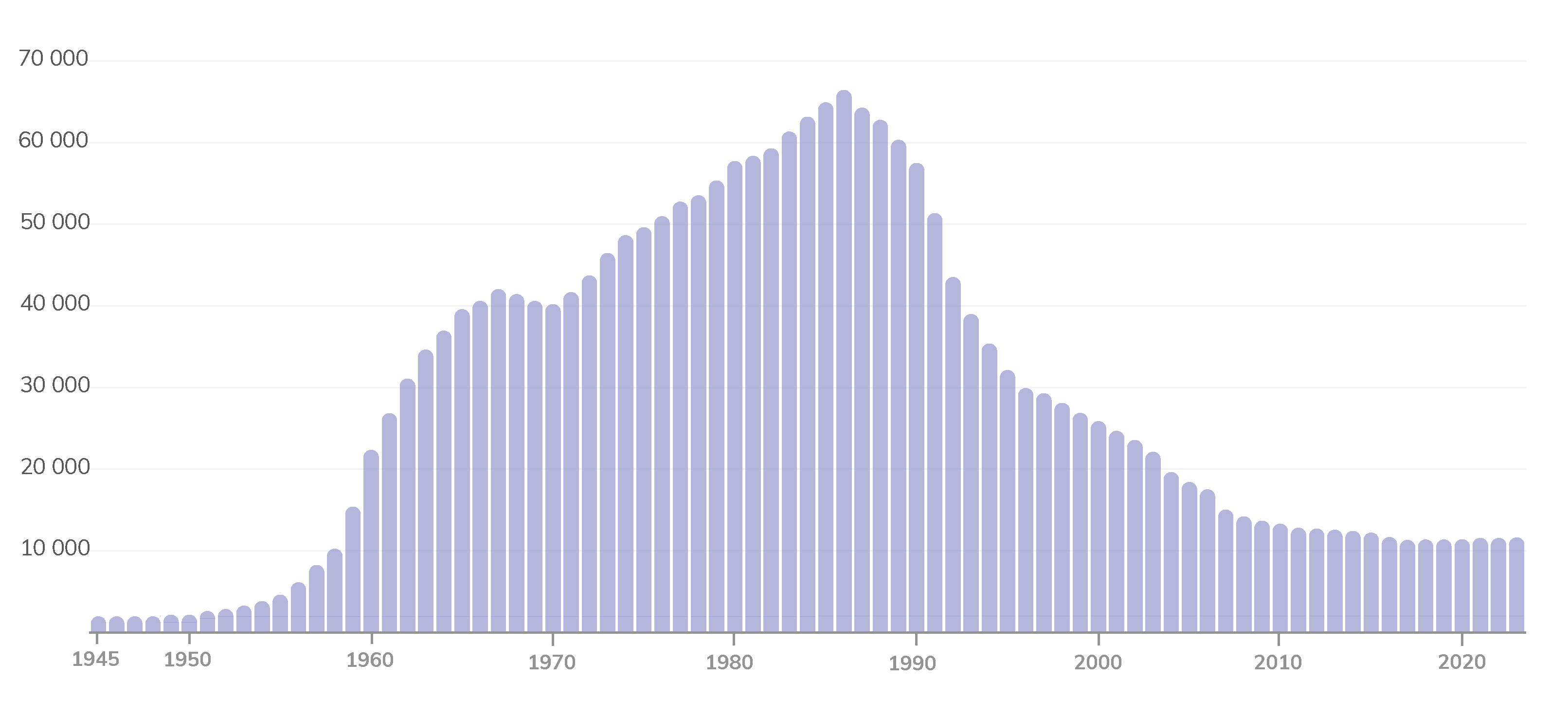

Figure 1.1. Nuclear arsenals of the world

For over 50 years, but especially since the end of the cold war, the United States and the Russian Federation (formerly the Soviet Union) have engaged in a series of bilateral arms control measures that have drastically reduced their strategic nuclear arsenals from a peak of around 60,000. The most recent of those measures, the New START Treaty, limits the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons to 1,550 per State. The Treaty is scheduled to expire on 4 February 2026; if it expires without a successor or is not extended, it will be the first time since the 1970s that the strategic arsenals of the United States and the Russian Federation have not been constrained.

Data source: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists' Nuclear Notebook, written by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, and Eliana Johns, Federation of American Scientists.

The prospect of an unprecedented three-way arms race gained further momentum in 2024. China faced mounting pressure to increase transparency and accountability around its nuclear arsenal amid widespread reports of a rapid quantitative expansion, which China continued to deny. The United States announced it would adapt its approach to arms control and non-proliferation for a new era “marked by evolving proliferation risks and rapid changes in technology”. This policy shift included preparing to compete with two nuclear peers for the first time, while reaffirming a determination to modernize both the country’s nuclear triad[1] and nuclear command, control and communications systems to “sustain, and if necessary, enhance [its] capabilities and posture”.

Regional tensions in 2024 continued to accelerate proliferation risks. Prospects for reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action became increasingly remote, with the Islamic Republic of Iran further advancing its nuclear programme while continuing not to provide the cooperation required by the IAEA. In November, the IAEA Board of Governors adopted a resolution requesting an updated assessment for March 2025 (GOV/2024/68), raising the likelihood of snapback sanctions under Security Council resolution 2231 (2015). Amid widening conflict with Israel, Iranian officials warned that their country could revisit its nuclear weapons policy and, if sanctions were reimposed, withdraw from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Nevertheless, talks held between France, Germany and the United Kingdom and the Islamic Republic of Iran in Geneva in November indicated continued interest in diplomatic solutions.

Nuclear risk in North-East Asia continued to rise throughout 2024, with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s ongoing advancement of its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes. During the year, the country test-fired 45 ballistic missiles of various ranges in contravention of the relevant Security Council resolutions — an increase since 2023, which had seen fewer than half of the 70 launches conducted in 2022. The missile activities in 2024 included launches of a new solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missile, three launches of intermediate-range ballistic missiles tipped with hypersonic glide vehicles and multiple independently targetable warheads, and several short-range ballistic missiles, including some fired in a large salvo. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea also undertook other activities in line with its 2021 five-year military development plan.

The fifth session of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction took place in New York in November, providing a platform for the participating States to reflect on past and future activities of the Conference and its working committee. Those States welcomed the procedural and substantive achievements made to date, acknowledging the success of their approach in making incremental and systematic substantive progress towards the development of a draft legally binding instrument.

All these issues came into sharp focus at the second session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 NPT Review Conference, held from 22 July to 2 August. Regional conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine and elsewhere were discussed primarily in the context of nuclear coercion and threats. The issue of transparency and accountability of nuclear-weapon States under the Treaty remained a central concern, with non-nuclear-weapon States expressing growing frustration over the lack of tangible progress on nuclear disarmament and mounting scepticism about nuclear-weapon States’ commitment to their disarmament obligations.

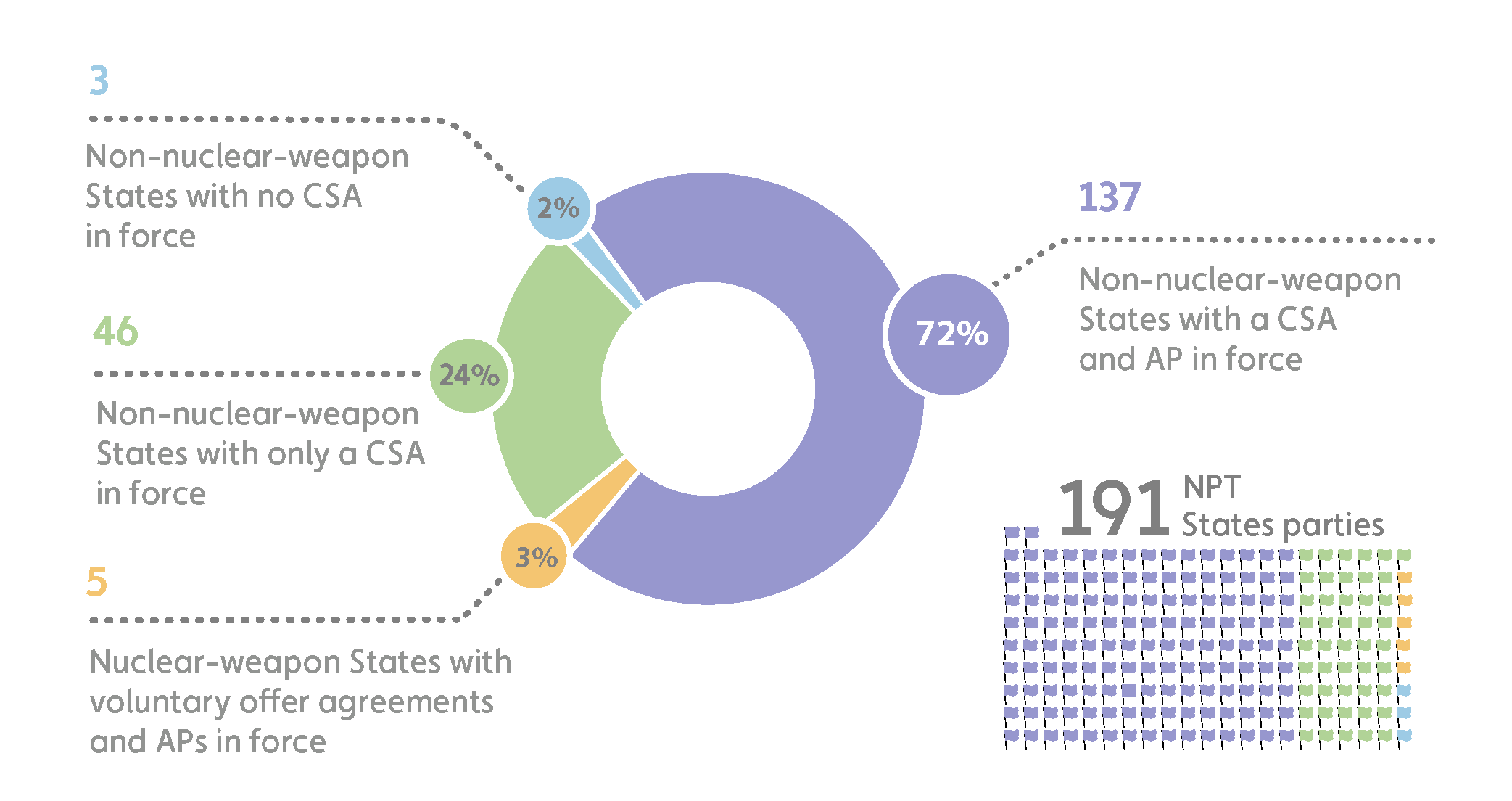

Figure 1.2. Status of safeguards agreements with States parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, as at 31 December 2024

Abbreviations: AP – additional protocol; CSA – comprehensive safeguards agreement.

The figure above summarizes the status of safeguards agreements and additional protocols in force with the IAEA and NPT States parties as at 31 December 2024. Safeguards agreements were in force with 188 NPT States parties, of which 183 are non-nuclear- weapon States with comprehensive safeguards agreements and five are nuclear-weapon States with voluntary offer agreements. Additional protocols were in force with 142 NPT States parties, including 137 States with comprehensive safeguards agreements and the five States with voluntary offer agreements. There were three NPT non-nuclear-weapon States that had not yet brought into force comprehensive safeguards agreements: Equatorial Guinea, Guinea and Somalia.

Data source: International Atomic Energy Agency.

States still demonstrated their commitment to working within the Treaty’s framework by putting forward various proposals to make concrete progress, although nuclear-weapon States received them with varying degrees of enthusiasm. The issue of “nuclear sharing” and extended deterrence arrangements gained prominence, exposing divisions among non-nuclear-weapon States. Many challenged the compatibility of such arrangements with the spirit — if not the letter — of the NPT, while criticizing non-nuclear-weapon States benefiting from these arrangements. Yet, despite these tensions, States parties showed continued willingness to explore new ideas for improving the review process.

In addition, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons expanded its membership with ratifications by Indonesia, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone and Solomon Islands. Informal working groups and facilitators advanced States parties’ implementation efforts through the Treaty’s intersessional process, which included the first informal consultations on the security concerns of States parties, coordinated by Austria. The Treaty’s Scientific Advisory Group continued its substantive work throughout 2024, including by establishing a scientific network to support the Treaty, which held an inaugural meeting in December.

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty also gained ratifications, with Papua New Guinea becoming the 178th State party in March. As concerns grew about the potential resumption of nuclear testing, States used the International Day Against Nuclear Tests (29 August) to reaffirm their support not only for the Treaty itself but for the broader norm against nuclear testing, emphasizing their determination to preserve that norm. The global focus on environmental and human impacts of past nuclear testing also continued to grow.

The General Assembly demonstrated ongoing commitment to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation by adopting several new mandates. By resolution 79/238, it established an independent Scientific Panel on the Effects of Nuclear War to examine the physical effects and societal consequences of nuclear war at local, regional and planetary scales. The Panel would conduct its work throughout 2025 and 2026, reporting to the General Assembly’s eighty-second session, in 2027. Through resolution 79/241, the Assembly also mandated the first comprehensive study on nuclear-weapon-free zones in nearly 50 years, with findings to be submitted at the body’s eighty-first session, in 2026.

Meanwhile, following the work of the Group of Governmental Experts to further consider nuclear disarmament verification issues, the General Assembly asked the Secretary-General, through resolution 79/240, to seek Member States’ written views on establishing a group of scientific and technical experts on nuclear disarmament verification within the United Nations. The Assembly also agreed to hold a one-day symposium in 2026 on victim assistance and environmental remediation in the context of the second resolution on addressing the legacy of nuclear weapons (resolution 79/60). These new mandates, emerging despite broader challenges to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, demonstrated that progress remained possible, however daunting the prospect.

Citizens of Oslo participate in a torchlight procession on 10 December in honour of Nihon Hidankyo's receipt of the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize. Nihon Hidankyo is a grass-roots organization of atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Credit: ICAN | Kaspar Fosser)

Issues related to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) is a landmark international treaty whose objectives are to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and further the goal of nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.

Second session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Preparatory Committee for the 2026 NPT Review Conference held its second session in Geneva from 22 July to 2 August, with Akan Rakhmetullin (Kazakhstan) serving as Chair. Representatives from 118 States parties, 12 international organizations and 72 non-governmental organizations participated in the session (for the list of participants, see NPT/CONF.2026/PC.II/INF/7). The Preparatory Committee adopted a procedural report (NPT/CONF.2026/PC.II/7).

The High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, in her opening statement to the Preparatory Committee, expressed her continued concern that cynicism about the efficacy of the Treaty will erode the many benefits it provides to its States parties. She suggested several priority issues that States could consider during their deliberations: (a) the accelerated implementation of existing commitments; (b) the notion that disarmament is not a reward for the resolution of security challenges, but rather a prerequisite for international peace and security; (c) ways to prevent nuclear war or any use of a nuclear weapon; (d) a recommitment to reinforcing the non-proliferation regime and supporting the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); and (e) ways to strengthen the linkage between the NPT and the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Preparatory Committee set aside six meetings for a general debate on issues related to all aspects of its work. It heard 89 statements by States parties and 21 statements by non-governmental organizations.

States parties reaffirmed the Treaty’s central role as the cornerstone of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. In that regard, they emphasized the Treaty’s vital contribution to international peace, security and stability. They also emphasized the importance of ensuring balanced implementation of the Treaty’s three pillars, while noting their mutually reinforcing nature.

National positions under the Treaty’s three pillars — disarmament, non-proliferation and peaceful uses of nuclear energy — revealed familiar fissures between States. Many States parties expressed frustration regarding the implementation of past commitments, particularly on nuclear disarmament and the 1995 resolution on the Middle East, as well as the perceived imbalance of obligations between the Treaty’s non-nuclear-weapon States and nuclear-weapon States. States parties recalled the necessity of implementing decisions 1 and 2 of the 1995 Review and Extension Conference of the Parties, as well as the resolution on the Middle East adopted at that meeting (NPT/CONF.1995/32 (Part I), annex); the final document adopted at the 2000 Review Conference (NPT/CONF.2000/28 (Parts I and II)); and the conclusions and recommendations for follow-on actions adopted at the 2010 Review Conference (NPT/CONF.2010/50 (Vol. I)).

Similar to the first session of the Preparatory Committee, the second session occasionally saw heated exchanges between States parties on geopolitical matters. Unsurprisingly, the war in Ukraine, the war in Gaza, the AUKUS partnership, the issue of nuclear sharing and extended deterrence, and the nuclear programme of the Islamic Republic of Iran emerged as areas of strong contention.

After the general exchange of views, the Preparatory Committee structured its work into three clusters, allocating equal time to each of the Treaty’s three pillars: (a) non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, disarmament and international peace and security; (b) non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, safeguards and nuclear-weapon-free zones; and (c) the inalienable right of all NPT States parties to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, without discrimination and in conformity with articles I and II of the Treaty. Each cluster addressed a distinct area of work, respectively: (a) nuclear disarmament and security assurances; (b) regional issues, including with respect to the Middle East and the implementation of the 1995 resolution on the Middle East; and (c) peaceful uses of nuclear energy and other provisions of the Treaty. The Preparatory Committee also conducted deliberations on the strengthened review process.

Cluster 1

States parties reaffirmed their commitment to the full and effective implementation of article VI of the Treaty, emphasizing that such implementation was essential for maintaining the Treaty’s credibility and provided an essential foundation for pursuing nuclear disarmament. States parties recalled past outcomes adopted by the 1995, 2000 and 2010 Review Conferences and emphasized that past commitments remained valid until implemented.

Numerous States parties expressed deep concern about the lack of progress in implementing disarmament obligations and commitments. They recalled the unequivocal undertaking made by the nuclear-weapon States in 2000, and reaffirmed in 2010, to accomplish the total elimination of their nuclear arsenals. Delegations stressed the need for efforts to reduce and ultimately eliminate nuclear arsenals, both deployed and non-deployed, through unilateral, bilateral, regional and multilateral measures conducted in a transparent, irreversible and internationally verifiable manner. States with the largest nuclear arsenals were encouraged to lead those efforts.

Many States parties argued that the deteriorating international security environment should not postpone nuclear disarmament, emphasizing the role of disarmament in reversing such deterioration.

Delegations expressed concern about the increased role of nuclear weapons in national and regional military doctrines; the qualitative and quantitative expansion and improvement of nuclear weapon arsenals; and the continuation of nuclear-weapon modernization programmes. States parties suggested such actions were not conducive to nuclear disarmament, as they contributed to arms racing and increased tensions, while signalling an intention to possess nuclear weapons indefinitely. Serious misgivings also arose around the growing use of nuclear rhetoric and threats to use nuclear weapons, including in the context of regional conflicts. In that regard, States parties recalled the prohibition, in Article 2, paragraph 4, of the Charter of the United Nations, on the threat or use of force. In addition, numerous delegations voiced apprehension about nuclear weapon-sharing arrangements, extended deterrence policies and the practice of stationing nuclear weapons on the territories of non-nuclear-weapon States.

The Preparatory Committee also continued to discuss the risk of the use of nuclear weapons, whether intentionally or by miscalculation, miscommunication, misperception or accident. The nuclear-weapon States, in cooperation with non-nuclear-weapon States, were called upon to take steps to prevent any use of nuclear weapons. Specific areas identified for action concerned resilient nuclear crisis communication channels, reduction of the operational readiness of nuclear weapon systems, transparency and restraint on doctrines and deployments, negative security assurances, and negotiations on nuclear arms control and disarmament. However, delegations emphasized that risk reduction cannot be a replacement for disarmament measures, but rather is a complement to ongoing disarmament efforts.

Many States parties recalled the joint statement of 3 January 2022, in which the leaders of the five nuclear-weapon States had affirmed that a nuclear war could not be won and must never be fought and had expressed their commitment to the obligations under the Treaty, including article VI. Delegations also reiterated the importance of negative security assurances by the nuclear-weapon States to all non-nuclear-weapon States parties pending the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

A significant number of States parties expressed concern about the catastrophic consequences of any use of nuclear weapons. They reaffirmed the need for all States to comply with applicable international law, including international humanitarian law, at all times. Some stressed that both the humanitarian consequences and the need to prevent nuclear-weapon use should underpin nuclear disarmament efforts. Several States parties also stressed the importance of providing victim assistance and addressing environmental contamination caused by nuclear weapon use and testing. Such assistance could include sharing technical and scientific information and providing financial support to help affected States Parties.

The Preparatory Committee heard many calls for the Russian Federation and the United States to return to fully implementing the Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START Treaty). Both countries heard calls to negotiate a follow-on treaty or a new nuclear arms control arrangement or instrument aimed at achieving further reductions in their nuclear arsenals, including non-strategic nuclear weapons. Other nuclear-weapon States were encouraged to join such negotiations.

States parties noted the continued inability of the Conference on Disarmament to commence negotiations on two key issues: a treaty banning the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices; and legally binding arrangements to assure non-nuclear-weapon States against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons by all nuclear-weapon States.

States parties that were also parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) noted its entry into force on 22 January 2021 and emphasized its complementarity with the NPT. In addition, many delegations reiterated the need for the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty as a core element of the international nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime.

Cluster 2

The Preparatory Committee emphasized IAEA safeguards as a fundamental component of the global nuclear non-proliferation regime — an essential aspect of peaceful nuclear commerce and cooperation contributing to both development and international collaboration on peaceful uses. In discussing the IAEA, many States parties said that nothing should undermine its authority or independence as the competent authority responsible for verifying and assuring compliance with safeguards agreements.

States parties underscored the critical importance of compliance with the NPT’s broader non-proliferation obligations, and they urged for the timely resolution of all safeguards non-compliance cases in full conformity with the IAEA Statute and States parties’ respective legal obligations. Voicing concern over non-compliance cases, delegations stressed the importance of ensuring that States either remain in compliance with their obligations or promptly return to compliance. They recalled the roles of the Security Council and the General Assembly in upholding safeguards compliance.

Delegations recalled the importance of applying IAEA safeguards pursuant to comprehensive safeguards agreements based on INFCIRC/153 (Corrected), welcoming that 182 NPT States parties had such agreements in force with the Agency. The Preparatory Committee encouraged States without such agreements to bring them into force as soon as possible.

Even as the Preparatory Committee recognized that comprehensive safeguards agreements provided assurances on declared nuclear material and a limited level of assurance concerning the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities, many States parties noted that implementing the model additional protocol (INFCIRC/540 (Corrected)) equipped the IAEA with broader information and access, enabling it to provide increased assurances in States that have an additional protocol in force. Participants stressed that a comprehensive safeguards agreement supplemented by an additional protocol therefore represents an enhanced verification standard, adding that it is the sovereign decision of any State to conclude an additional protocol. The Preparatory Committee noted that 141 States parties had brought additional protocols into force.

Regarding States in comprehensive safeguards agreements with operative small quantities protocols based on the original standard text, the Preparatory Committee noted that such arrangements significantly affect the IAEA’s ability to draw credible and sound annual safeguards conclusions. Delegations called upon States that had not yet amended or rescinded their original small quantities protocols to do so as a matter of urgency.

Many States parties expressed grave concern regarding military activities conducted near or at nuclear sites under IAEA safeguards, citing their negative impact on nuclear safety, security and safeguards, as well as the implications when competent authorities lose control over such locations.

The Preparatory Committee continued to debate naval nuclear propulsion and its implications for safeguards and the integrity of the global non-proliferation regime. Several States parties took note of discussions at the IAEA Board of Governors concerning safeguards arrangements related to naval nuclear propulsion.

The Preparatory Committee recognized that the responsibility for nuclear security within a State rests entirely with that State. Participants reaffirmed that nuclear security measures — including physical protection of all nuclear material and facilities from unauthorized access, unauthorized removal and sabotage, as well as computer security — all support the Treaty’s aims.

States parties continued to express concern over existing and emerging terrorist threats, including the risk that non-State actors might acquire nuclear weapons and their means of delivery. Recalling the essential role of relevant Security Council resolutions, including resolution 1540 (2004), delegations emphasized every State’s obligation to implement their binding provisions.

States parties stressed the need to ensure that exports of nuclear-related dual-use items do not support the proliferation of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices. They also recalled the legitimate right of all States parties, in particular developing States, to have full access to nuclear material, equipment and technological information for peaceful purposes. Delegations stressed the importance of facilitating transfers of nuclear technology and international cooperation in conformity with the NPT, while eliminating any undue constraints inconsistent with the Treaty.

The Preparatory Committee reaffirmed that internationally recognized nuclear-weapon-free zones, established on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at by the States of the region concerned, enhance international and regional peace and security, strengthen the global nuclear non-proliferation regime and contribute towards realizing the objectives of nuclear disarmament. In that context, States parties acknowledged the contributions of the Antarctic Treaty, the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (Treaty of Tlatelolco), the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty (Rarotonga Treaty), the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone (Bangkok Treaty), the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (Pelindaba Treaty) and the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia, as well as the nuclear-weapon-free status of Mongolia.

States called for further progress by nuclear-weapon States on ratifying the relevant protocols to nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties, which include negative security assurances. To that end, delegations welcomed the stated readiness of the nuclear-weapon States and the member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to engage in constructive consultations on the outstanding issues related to signing and ratifying the Protocol to the Bangkok Treaty. Nuclear-weapon States also heard calls to review any reservations or interpretative statements made upon ratifying such protocols and to engage in relevant dialogue with zone members.

The Preparatory Committee discussed the importance of advancing the full implementation of the resolution on the Middle East adopted by the NPT Review and Extension Conference in 1995 (NPT/CONF.1995/32 (Part I), annex). Delegations argued that the 1995 resolution remained valid until its goals and objectives were achieved, noting it was an essential element of the outcome of the 1995 Conference and the basis on which the NPT was indefinitely extended without a vote. States also acknowledged the developments at the first four sessions of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction, held from 2019 to 2023 at United Nations Headquarters.

Delegations underscored the importance of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) endorsed by the Security Council in resolution 2231 (2015) and urged all parties to return to its full implementation.

The Preparatory Committee also discussed the lack of progress in resolving the long-outstanding safeguards issues concerning the Syrian Arab Republic, emphasizing the importance of the country’s effective cooperation with the IAEA.

A large group of States parties reaffirmed their unwavering support for the complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. Expressing grave concern about the continued advancement of the nuclear and ballistic missile programmes of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the group condemned its six nuclear tests to date and stressed that it must not conduct further tests. The countries emphasized that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea could not have the status of a nuclear-weapon State pursuant to the NPT, and called on it to return, without delay, to the Treaty and the application of IAEA safeguards on all of its nuclear activities. In that connection, 77 States parties released a joint statement on “addressing the North Korean nuclear challenge” (NPT/CONF.2026/PC.II/WP.39).

Cluster 3

The Preparatory Committee reaffirmed that nothing in the NPT should be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of all parties to develop, research, produce and use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination and in conformity with articles I, II, III and IV of the NPT. Delegations emphasized that all States parties should undertake to facilitate, and had the right to participate in, the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials, and scientific and technological information for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy in conformity with all the Treaty’s provisions.

Delegations reaffirmed the right of each State party to define its national energy policy. For those wishing to pursue nuclear power, the Committee noted that nuclear technologies and innovations — including advanced reactors, small and modular reactors, as well as large-capacity power reactors and fast-neutron reactors — could play an important role in facilitating energy security, decarbonization and transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Delegations encouraged States parties in a position to do so to cooperate in contributing to the further development of peaceful nuclear energy applications, especially in the territories of non-nuclear-weapon States parties, with due consideration for the needs of the developing areas of the world.

States parties underscored the importance of nuclear safety and nuclear security for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. The Committee noted that, when developing nuclear energy, including nuclear power, its use must be accompanied by commitments to and the ongoing implementation of IAEA safeguards, as well as appropriate and effective levels of safety and security, consistent with States parties’ national legislation and respective international obligations. Delegations stressed that high levels of safety and security should be ensured in the deployment of new and emerging nuclear technologies, and that the development of advanced reactors and small and modular reactors should proceed in a safe, secure and safeguarded manner.

The Committee discussed how regional and cooperative agreements to promote the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, including under the auspices of the IAEA, could provide an effective means to facilitate technical and technology transfers. States parties also considered the importance of transporting radioactive materials consistent with relevant international standards of safety, security and environmental protection. Delegations encouraged continued efforts to improve communication between shipping and coastal States to build confidence and address concerns regarding transport safety, security and emergency preparedness.

Numerous States parties emphasized the importance of nuclear safety and security regarding peaceful nuclear facilities and materials in all circumstances, including in armed conflict zones. Delegations voiced strong support for the IAEA’s efforts in that regard, noting the IAEA Director General’s seven indispensable pillars for ensuring nuclear safety and security during an armed conflict, as well as the five concrete principles to help to ensure nuclear safety and security at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant.

The Committee also noted the IAEA Comprehensive Report on the Safety Review of the ALPS-treated Water at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, with various States parties stressing the importance of the IAEA’s impartial, independent and objective safety review and monitoring based on relevant safety standards in all phases.

Emphasizing the critical role of nuclear science and technology in achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement on climate change, delegations acknowledged the importance of assistance, particularly for developing countries and least developed countries. States noted such assistance could occur through capacity-building, the provision of equipment, the strengthening of regional networking and regional cooperation frameworks and through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation.

In that context, the Committee stressed the essential role of the IAEA, including through its technical cooperation programme, in assisting States parties, upon request, to build human and institutional capacities, including regulatory capabilities, for the safe, secure and peaceful applications of nuclear science and technology. States added that such assistance contributed to meeting energy needs, improving human and animal health, combating poverty, protecting the environment, developing agriculture, managing the use of water resources, optimizing industrial processes and preserving cultural heritage.

The Committee also discussed the importance of IAEA technical cooperation activities and nuclear knowledge-sharing, as well as the transfer of nuclear technology to developing countries and least developed countries. States parties emphasized the importance of sharing nuclear knowledge and transferring nuclear technology to developing countries and least developed countries. To this end, the Committee recognized the need to ensure that the IAEA had adequate and necessary support to enable it to provide, upon request, the assistance needed by member States. States parties welcomed the role of the IAEA Peaceful Uses Initiative in mobilizing extrabudgetary contributions.

Strengthened review process

The second session of the Preparatory Committee continued discussions on improving the NPT’s implementation by strengthening the Treaty’s review process, building upon the deliberations of the July 2023 working group convened to that end. Although the 2023 working group did not reach consensus on recommendations to the Preparatory Committee, States parties recognized its value in deepening substantive discussions on measures to enhance the Treaty’s review mechanisms.

In 2024, the Preparatory Committee continued to exchange views on specific proposals to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, transparency, accountability, coordination and continuity of the review process. Proposals for improving efficiency and effectiveness included more effective time management and avoiding duplicative and overlapping discussions. Delegations also expressed support for interactive debates, incorporating a rolling text in sessions of the Preparatory Committee, and measures to strengthen coordination between those sessions and the Review Conference.

States parties discussed possible steps to bolster transparency and accountability on the implementation of disarmament obligations. Participants suggested that establishing benchmarks and timelines could help to gauge progress and improve accountability in the implementation of nuclear disarmament obligations and commitments. Many delegations also called for regular, standardized reporting by nuclear-weapon States, as well as the allocation of time during the formal sessions of the Treaty’s review cycle to review and discuss the reports.

Issues related to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty prohibits nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere: on the Earth’s surface, in the atmosphere, underwater and underground. The Treaty opened for signature in New York on 24 September 1996. It will enter into force after it is ratified by all 44 States listed in its annex 2.

Challenges to the international norm against nuclear testing

The year 2024 opened under the shadow of the Russian Federation’s decision in November 2023 to revoke its ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, deepening divisions among nuclear-weapon States and challenging their commitment to the international norm against nuclear testing.

The tensions were compounded by a report from a non-governmental organization detailing increased activities at key nuclear test sites in recent years. Commercial satellite imagery released in September revealed heightened activity at the Russian Federation’s Novaya Zemlya test site, with a senior Russian official subsequently declaring the site “fully ready” for testing operations. The Russian Federation reaffirmed its conditional moratorium on nuclear testing, stating that it would not conduct tests unless the United States did so first.

Progress towards universalization

Nonetheless, the year saw several encouraging developments. In March, Papua New Guinea ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, becoming the 178th ratifying State. This milestone underscored continued global support for the Treaty and the commitment of smaller States to the global moratorium.

The Provisional Technical Secretariat of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, operating with the support of signatory and ratifying States, continued to strengthen both the Treaty’s universalization efforts and its verification regime. The International Monitoring System, which comprised over 300 monitoring facilities worldwide at the end of 2024, remained a powerful deterrent against clandestine nuclear testing, providing near real-time data on seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound and radionuclide activities that could indicate nuclear explosions.

International Day against Nuclear Tests

On 4 September, during the General Assembly’s high-level plenary session commemorating the International Day against Nuclear Tests (29 August),[2] Member States reiterated their commitment to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and the imperative of eradicating nuclear testing once and for all. Many States voiced profound concern over the growing risk that a return to nuclear testing would reverse decades of progress towards establishing a universal norm against such activities. Speakers frequently referenced the Russian Federation’s withdrawal of its ratification, while citing broader geopolitical tensions and increasingly strident nuclear rhetoric as contributors to an environment that could facilitate a resumption of nuclear testing.

Addressing the Assembly, the Director and Deputy to the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs delivered a pointed appeal to the international community to reinforce its commitment to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. He emphasized the critical deterrent effect of the Treaty’s global verification regime, while issuing a call to the remaining Annex 2 States to demonstrate leadership by ratifying the Treaty promptly and without preconditions.

The commemorative session also provided a forum for addressing the historical consequences of nuclear testing on affected communities worldwide. Multiple speakers highlighted the devastating and persistent effects of past nuclear tests on health, the environment and human rights, stressing that nuclear testing has caused irreversible damage across generations. Speakers pressed for stronger international efforts to address those enduring legacies, urging accountability from States responsible for past nuclear tests and emphasizing the need for the full implementation of victim assistance and environmental remediation measures. (For more information, see chap. 8.)

Ministerial Meeting of the Friends of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

Australia’s Foreign Minister, Penelope Wong, chaired the eleventh Ministerial Meeting of the Friends of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty on 24 September during the high-level week of the General Assembly’s seventy-ninth session. The meeting brought together the group’s six member countries — Australia, Canada, Finland, Germany, Japan and the Kingdom of the Netherlands — alongside senior officials from ratifying and signatory States.[3]

Participants emphasized the urgency of the Treaty’s entry into force. In its final declaration, the Meeting reaffirmed the Treaty’s critical role in global security, expressed concern over recent challenges to the global test ban regime, urged all remaining Annex 2 States to ratify the Treaty, and called on all States to declare or maintain national moratoriums on nuclear-weapon test explosions and any other nuclear explosions.

In her remarks to the Meeting, the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs underscored the urgent need to uphold the norm against nuclear testing amid rising geopolitical tensions and intensifying nuclear rhetoric. While acknowledging progress since the previous Ministerial Meeting, in 2022, including five new ratifications and one signature of the Treaty, she stressed that voluntary moratoriums remain insufficient without the Treaty’s entry into force. The High Representative called on all States, particularly Annex 2 States, to ratify the Treaty without conditions and reiterated the Secretary-General’s appeal for nuclear-weapon States to reaffirm their testing moratoriums. She also highlighted the General Assembly resolution adopted in 2023 on addressing the legacy of nuclear weapons (78/240) as a critical step towards victim assistance and environmental remediation.

Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

The TPNW, adopted in 2017, includes a comprehensive set of prohibitions on participating in any nuclear-weapon activity. It entered into force on 22 January 2021, following the deposit of the fiftieth instrument of ratification or accession with the Secretary-General on 24 October 2020.

Signature and ratification

The TPNW continued to expand its membership in 2024. On 24 September, during a high-level ceremony at the United Nations held during the seventy-ninth session of the General Assembly, Indonesia, Sierra Leone and Solomon Islands ratified the Treaty. These accessions brought the total number of States parties to 73, with 94 signatories, further demonstrating the growing international commitment to the Treaty’s objectives and the broader goal of nuclear disarmament.

Intersessional process

States parties remained actively engaged in intersessional work throughout 2024, in accordance with decision 1 of the second Meeting of States Parties, in 2023 (TPNW/MSP/2023/14, annex II). The intersessional process continued through multiple informal working groups and facilitators, with each focusing on specific aspects of the Treaty’s implementation, while preparing reports to the third Meeting of States Parties.

South Africa and Uruguay co-chaired efforts on universalization, while Kazakhstan and Kiribati led discussions on victim assistance, environmental remediation and international cooperation. Malaysia and New Zealand co-chaired the working group on the implementation of article 4, particularly regarding the future designation of a competent international authority for overseeing nuclear disarmament and verification processes. Mexico supported the integration of gender perspectives into Treaty implementation as the gender focal point, and Ireland and Thailand acted as informal facilitators to ensure the Treaty’s complementarity with the broader nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime. These coordinated efforts reinforced collaboration among States parties and advanced Treaty implementation ahead of the third Meeting of States Parties, scheduled for 2025.

Additionally, Austria coordinated a new consultative process on the security concerns of States under the Treaty, established by decision 5 of the second Meeting of States Parties (TPNW/MSP/2023/14, annex II). This process involved engagement with States, experts and civil society organizations to (a) articulate the security concerns stemming from the existence of nuclear weapons and the doctrine of nuclear deterrence; and (b) challenge the deterrence-based security paradigm with new scientific evidence on the humanitarian consequences and risks of nuclear weapons. The process was expected to result in a report containing key recommendations to the third Meeting of States Parties.

Scientific Advisory Group

The Scientific Advisory Group continued to fulfil its mandate of providing independent technical expertise to support the Treaty’s implementation and inform decision-making. Established by the first Meeting of States Parties in 2022 and appointed by the President of the second Meeting of States Parties in 2023, the Group is also tasked to assess developments relevant to nuclear disarmament and humanitarian impacts, support capacity-building among States parties and facilitate engagement with scientists, academia and civil society to strengthen the Treaty’s objectives (TPNW/MSP/2022/6, annex III).

Throughout 2024, the Scientific Advisory Group held regular monthly meetings aimed at building upon the Treaty’s technical and scientific foundations. Participants provided updates, explored relevant themes on nuclear disarmament and focused on developing in-depth analysis, including a substantive report for the third Meeting of States Parties. The Group also contributed to discussions within the informal working groups on key provisions of the Treaty, including nuclear risk reduction, victim assistance and environmental remediation.

In a significant milestone, the Group led the establishment of a scientific network in accordance with its mandate to “identify and engage scientific and technical institutions in States Parties and more broadly to establish a network of experts to support the goals of the Treaty” (TPNW/MSP/2022/6, annex III). The scientific network held its inaugural meeting on 9 December, establishing a platform for interdisciplinary research and global scientific engagement to advance the Treaty’s objectives. Its specific aims included supporting implementation of the Treaty through research, knowledge-sharing and science-based initiatives, while expanding participation from the global scientific community.

Preparations for the third Meeting of States Parties

The Coordination Committee convened regularly throughout 2024 to oversee the workplans of the intersessional process, monitor progress across various workstreams and assess work conducted by the Scientific Advisory Group. It held deliberations under the leadership of Akan Rakhmetullin (Kazakhstan), President of the third Meeting of States Parties (TPNW/MSP/2023/14, para. 24).

On 29 August, coinciding with the International Day against Nuclear Tests, the President hosted a Coordination Committee retreat in Astana as part of the Treaty’s intersessional programme of work. The retreat provided an opportunity for dialogue and exchange of ideas on key priorities for the third Meeting of States Parties. Discussions focused on ensuring the Treaty’s full and effective implementation, advancing universalization efforts and developing tangible forms of assistance to address the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. The retreat also explored the establishment of an international trust fund for States parties affected by nuclear weapons testing; potential outcomes of the third Meeting of States Parties; and milestones leading up to the first Review Conference of the Treaty in 2026.

The third Meeting of States Parties was scheduled to be held from 3 to 7 March 2025 at United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Bilateral agreements and other issues

Implementation of the New START Treaty

On 5 February 2018, the United States and the Russian Federation met the central limits of the New START Treaty. Under the Treaty, the parties must possess no more than 700 deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles and heavy bombers, and no more than 1,550 warheads associated with those deployed launchers.

In an address to the Russian Federal Assembly on 21 February 2023, the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, announced that the country was “suspending its participation” in the Treaty. In a subsequent statement, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that the Russian Federation intended to strictly comply with the quantitative restrictions on strategic offensive arms within the Treaty’s life cycle.

During 2024, senior Russian and United States officials reaffirmed both parties’ commitment to adhering to those quantitative restrictions. However, neither party participated in the biannual data exchange on Treaty-accountable items in 2024 and both parties raised concerns over the other’s compliance with the Treaty limitations, which could not be verified due to the lack of information exchange and the halting of inspections. On 27 June, Russian Foreign Deputy Minister Sergey Ryabkov said that there was no certainty that the United States was adhering to the New START ceilings. The United States Department of State, in its 2024 Report to Congress on Implementation of the New START Treaty, asserted that the United States could not certify the Russian Federation to be complying with the terms of the Treaty. Moreover, the United States assessed with high confidence that while the Russian Federation had not engaged in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits, it was probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of the year and may have slightly exceeded that limit in some instances.

The Russian Federation and the United States both reaffirmed their pledges to continue to comply with the 1988 Ballistic Missile Launch Notifications Agreement, which provides for obligations to provide mutual notifications of intercontinental ballistic missile and submarine-launched ballistic missile launches.

As was the case in 2023, the parties convened no meetings of the Bilateral Consultative Commission in 2024, with the Russian Federation maintaining that it could not resume the strategic dialogue without taking into account the overall global security outlook and the strategic stability issue. However, both parties had expressed willingness to resume dialogue on strategic stability in the future.

The New START Treaty is the last remaining bilateral strategic nuclear arms control agreement. If it expires on 4 February 2026 without a successor arrangement in place, there will be no limitations on the strategic nuclear arsenals of the United States and the Russian Federation for the first time in five decades.

Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and Security Council resolution 2231 (2015)

The situation surrounding the JCPOA remained fragile throughout 2024. The Islamic Republic of Iran, which had begun progressively to reduce its JCPOA undertakings in July 2020 following the unilateral withdrawal of the United States two years earlier, continued to significantly limit its cooperation with the IAEA in resolving outstanding safeguards issues. This resulted in the adoption of two resolutions by the IAEA Board of Governors in June and November (GOV/2024/39 and GOV/2024/68).

Addressing the General Assembly at United Nations Headquarters on 24 September, the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, signalled a potential change in approach, stating that “we have the opportunity to … enter a new era” and that “[w]e are ready to engage with JCPOA participants”. This message marked a clear departure from the approach of his predecessor, who had said at the same venue in 2022 that the United States had “trampled on the accord” and that his country could not trust the United States to meet its commitments without “guarantees and assurances”.

However, following Israeli airstrikes against Iranian territory in October, and the November IAEA Board of Governors’ resolution on safeguards implementation, several senior Iranian officials made statements alluding to their country’s capability to produce nuclear weapons and hinting at a possible review of its military doctrine prohibiting nuclear weapons possession. On 27 November, Iranian Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Araghchi stated in an interview that his country already had the capability and knowledge to create nuclear weapons. He warned that if previous Security Council sanctions were reimposed through the JCPOA’s snapback mechanism, the Islamic Republic of Iran would probably change both its current policy on cooperation with the West on nuclear issues and its prohibition on possessing nuclear weapons. Additionally, on 9 October, 39 members of the Iranian parliament (Majlis) wrote to the Supreme National Security Council requesting a review of Iranian self-defence doctrine to permit nuclear weapons development.

According to news reports, the Israeli airstrikes on 26 October successfully targeted a facility in Parchin containing equipment needed to design and test explosives for a nuclear weapon. The destroyed equipment reportedly dated to the early 2000s and had been stored in the facility since that time. Media reports also indicated that the United States had expressed serious concerns to the Islamic Republic of Iran about research activities in the country that could support nuclear weapons production.

Notably, the United States Office of the Director of National Intelligence removed long-standing language from an August 2024 report to Congress. Previous reports since 2019 had consistently stated that the Islamic Republic of Iran “is not currently undertaking the key nuclear weapons-development activities necessary to produce a testable nuclear device”. The revised assessment instead said that the country had “undertaken activities that better position it to produce a nuclear device, if it chooses to do so”.

Nuclear activities by the Islamic Republic of Iran

In 2024, the IAEA continued to report to its Board of Governors and the Security Council on the Islamic Republic of Iran’s implementation of nuclear-related commitments under the JCPOA, as well as on verification and monitoring matters in view of Security Council resolution 2231 (2015).

According to the IAEA’s final report of the year on the matter (GOV/2024/61), the Islamic Republic of Iran had significantly expanded its uranium stockpiles. As of 26 October, the country had accumulated an estimated 5,807.2 kg of uranium hexafluoride (UF-6) enriched to various levels, including 182.3 kg of uranium enriched to 60 per cent U-235 and 839.2 kg of uranium enriched to 20 per cent U-235.

This represented a substantial increase since October 2023, the total enriched uranium stockpile having grown by 1,676.5 kg — a 40.5 per cent increase. The growth included 54 kg more uranium enriched to 60 per cent U-235 (a 42.1 per cent increase) and 272.1 kg more uranium enriched to 20 per cent U-235 (a 48 per cent increase). Under the JCPOA, the Islamic Republic of Iran had committed not to accumulate more than 202.8 kg of uranium enriched to 3.67 per cent U-235.

On 14 November in Tehran, the IAEA Director General met with President Masoud Pezeshkian, the Vice-President and head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Mohammad Eslami, and the Foreign Minister, Abbas Araghchi. During the meetings, they discussed the possibility of the Islamic Republic of Iran not further expanding its 60 per cent enriched uranium stockpile, including technical verification measures necessary for the IAEA to confirm such an arrangement.

Initial progress appeared promising. On 16 November, at both the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant and the Fuel Enrichment Plant in Natanz, the IAEA verified that the country had begun to implement preparatory measures aimed at stopping the increase of its stockpile of uranium enriched up to 60 per cent U-235.

However, this cooperation proved short-lived. On 2 December, shortly after the IAEA Board of Governors adopted its second resolution of the year on Iranian safeguards implementation (GOV/2024/68), the Islamic Republic of Iran announced operational adjustments at the Fordow plant that would dramatically accelerate production of uranium enriched to 60 per cent U-235. By beginning with feedstock already enriched to 20 per cent UF-6, rather than 5 per cent UF-6, the IAEA assessed that the Islamic Republic of Iran would be able to produce 34 kg of 60 per cent enriched uranium per month at Fordow — a more than sevenfold increase of the previous rate of approximately 4.7 kg per month, as later reported to the Board of Governors (GOV/2025/8).

Beyond increasing production rates, the Islamic Republic of Iran also expanded its overall enrichment capacity by adding and starting operation of more advanced centrifuge cascades. In October, the country was operating six additional IR-2m centrifuge cascades and nine additional IR-4 centrifuge cascades at the Fuel Enrichment Plant in Natanz, as well as one additional IR-5 centrifuge cascade at the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant.

On 28 November, the Islamic Republic of Iran informed the IAEA of plans for a significant further expansion of its uranium enrichment capacity. The intended additions included 18 new IR-4 centrifuge cascades at the Fuel Enrichment Plant, 14 new cascades incorporating various centrifuge types (IR-2m, IR-4 and IR-6) at the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant, as well as one IR-6 cascade containing up to 1,152 centrifuges — about seven times larger than an average-sized cascade. Once operational, the new cascades were expected to potentially increase the country’s uranium enrichment capacity by more than twofold.

Verification and monitoring

In 2024, the Islamic Republic of Iran maintained its suspension of voluntary transparency measures contained in the JCPOA. The affected measures included provisions of the additional protocol to the country’s comprehensive safeguards agreement, as well as modified code 3.1 of the subsidiary arrangements to its safeguards agreement, both of which the Government had ceased implementing in February 2021. Furthermore, IAEA surveillance and monitoring equipment related to the JCPOA removed by the Islamic Republic of Iran in June 2022 was not reinstalled and remained inoperative.

These restrictions significantly impaired the IAEA's verification activities. Since February 2021, the Agency had been unable to perform verification and monitoring of various JCPOA-related activities, including Iranian production and possession of centrifuges, rotors and bellows, heavy water, and uranium ore concentrate.

The IAEA emphasized it had lost continuity of knowledge regarding the production and current inventory of those materials — a loss that could not be restored. Additionally, removal of the IAEA’s surveillance and monitoring equipment had created “detrimental implications for the Agency’s ability to provide assurance of the peaceful nature of the country’s nuclear programme”.

During high-level meetings between the IAEA and Iranian officials in Tehran on 14 November, the Islamic Republic of Iran agreed to consider accepting the designation of four additional experienced inspectors. This was in response to the Agency’s concerns that the country had withdrawn the designation of several experienced inspectors in September 2023. The IAEA noted at the time that while the withdrawal was formally permitted under the NPT Safeguards Agreement of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Government had taken the measure “in a manner that directly and seriously affects the Agency’s ability to conduct effectively its verification activities in Iran, in particular at the enrichment facilities”.

Implementation of Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty safeguards

In 2024, the IAEA continued its quarterly reporting on the implementation of its 1974 safeguards agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran in connection with the NPT and the additional protocol provisionally applied by the Government pending its entry into force.

Since 2019, the Agency had been seeking clarifications from the country regarding information related to anthropogenic uranium particles and possible undeclared nuclear material and nuclear-related activities at four locations that had not been declared. These outstanding safeguards issues are believed to be connected to the Islamic Republic of Iran’s nuclear-related activities dating back to the early 2000s.

Following exchanges between the sides, the IAEA reported that it “had no additional questions” on two of the four locations — identified as “Lavisan-Shian” and “Marivan” — and the issues at those sites were “no longer outstanding” as of March 2022 and May 2023, respectively. The IAEA persisted in seeking clarifications regarding two remaining locations, identified as “Varamin” and “Turquzabad”.

In its report dated 27 May (GOV/2024/29), the IAEA reported an Iranian assertion that there had “never been any undeclared location which is required to be declared under the [comprehensive safeguards agreement]” in Varamin, and that there “has not been any nuclear activity or storage” at Turquzabad.

On 5 June, the IAEA Board of Governors adopted a draft resolution on the Islamic Republic of Iran (GOV/2025/38) by a vote of 20 in favour, 2 against and 12 abstentions[4] — a substantial increase in abstentions from the 5 recorded on the previous such resolution in November 2022 (GOV/2022/70). In the new resolution, the Board noted that despite previous resolutions on the matter and the IAEA’s continued efforts, the Islamic Republic of Iran had not yet fully clarified the remaining outstanding safeguards issues, and called on the country to cooperate with the IAEA and resolve those matters.

Following the IAEA’s report of 19 November (GOV/2024/62), which showed continued lack of progress, the Board of Governors adopted another resolution on 21 November (GOV/2024/68), tabled by France, Germany and the United Kingdom (the E3), as well as the United States. In the resolution — adopted by a vote of 19 in favour, 3 against and 12 abstentions[5] — the Board again noted that the Islamic Republic of Iran had not yet fully clarified the remaining outstanding safeguards issues with the IAEA. Significantly, in operative paragraph 6, the Board requested the IAEA to “produce a comprehensive and updated assessment on the possible presence or use of undeclared nuclear material in connection with past and present outstanding issues regarding Iran’s nuclear programme”, to be submitted by the next Board meeting in March 2025 or “at the latest by spring 2025”.

Implementation of Security Council resolution 2231 (2015)

By its resolution 2231 (2015) on the JCPOA, the Security Council requested the Secretary-General to report every six months on the resolution’s implementation. In his seventeenth (S/2024/471) and eighteenth (S/2024/896) reports, issued on 19 June and 12 December respectively, the Secretary-General focused on the resolution’s remaining provisions concerning restrictions applicable to nuclear-related activities. Restrictions related to ballistic missile activities, transfer of conventional arms to and from the Islamic Republic of Iran, asset freezes and travel bans had been lifted in previous years, in line with their respective provisions.

The Secretary-General noted in his reports that no new proposals to participate in or permit the activities set forth in paragraph 2 of annex B to resolution 2231 (2015) had been submitted to the Security Council in 2024. However, a total of 18 new notifications were received during the year for certain nuclear-related activities consistent with the JCPOA that do not require approval by the Council but must be reported to it.

In his eighteenth report, the Secretary-General observed that the regional context surrounding the JCPOA had deteriorated, which underscored the critical need for a peaceful solution to the Iranian nuclear issue. Noting that 2025 would mark the final year of implementation of resolution 2231 (2015), he urged JCPOA participants and the United States to remain committed to a diplomatic solution for restoring the objectives of the JCPOA and to prioritize multilateralism and diplomacy.

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea continued its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes in 2024. The country launched 45 ballistic missiles of various ranges in contravention of the relevant Security Council resolutions,[6] continuing a trend of frequent launches that began in 2022, when the country conducted 70 launches — its most ever in a single year — after averaging 11.8 annual launches over the preceding five years.

The country’s 2024 activities included a test flight of a new solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missile, three launches of intermediate-range ballistic missiles tipped with hypersonic glide vehicles and multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles, and numerous short-range ballistic missile launches, some conducted in large salvos. Meanwhile, it undertook other activities in line with the five-year military development plan unveiled at its eighth Party Congress in January 2021.

Ballistic missile launches

On 31 October, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea launched a “Hwasong-19” intercontinental ballistic missile. With a flight time of 85 minutes and 56 seconds, the missile flew a distance of 1,001.2 km and reached an altitude of over 7,687.5 km before falling into the sea. Those figures set new records for both flight duration and maximum altitude for the country’s intercontinental ballistic missile launches. The Hwasong-19 is the second solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missile developed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, following the Hwasong-18, which was first launched in April 2023 and tested twice more that year. Solid-propellant missiles offer significant operational advantages, as they do not need to undergo fuelling before launch and thus can be prepared more quickly than liquid-propellant missiles, while being harder to detect in advance.

On 14 January, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea launched a solid-fuel intermediate-range ballistic missile loaded with what it described as a hypersonic manoeuvrable controlled warhead — an apparent reference to a manoeuvrable re-entry vehicle capable of manoeuvring and changing its trajectory. Its flight, which ended in waters near the east coast of the Korean Peninsula, followed the country’s announcement in November 2023 that it had carried out two successful tests of a new engine for a solid-fuel intermediate-range ballistic missile. According to open-source information, its previously developed intermediate-range ballistic missile, the Hwasong-12 — first tested in 2017 and twice more in 2022 — uses liquid propulsion.

On 2 April, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea launched a Hwasong-16B intermediate-range ballistic missile equipped with what it called a “hypersonic glide flight combat unit”. According to the country’s state media, this marked the first launch of the new weapon system, with the missile following its predetermined flight trajectory before landing off the eastern Korean Peninsula.

On 26 June, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea conducted a ballistic missile launch that reportedly exploded shortly after take-off. However, the country claimed that it had successfully conducted “the separation and guidance control test of individual mobile warheads” using the first-stage engine of an intermediate-range ballistic missile. The event appeared to indicate the country’s intention to acquire a multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle capability, as outlined in its five-year military plan.

In addition, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea conducted multiple “salvo” launches of short-range ballistic missiles, on 18 March, 22 April and 30 May. The 30 May launch reportedly involved 18 such missiles. Additionally, the country’s state media reported the launch of a “tactical ballistic missile” on 17 May to test “a new autonomous navigation system”.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea also conducted several cruise missile launches in 2024. Its state media reported the first test launch of a “new-type strategic cruise missile” called the “Pulhwasal-3-31” on 24 January and 28 January, describing it as a submarine-launched cruise missile. On 2 February, the country launched cruise missiles carrying what it termed “super-large” warheads. While cruise missiles are not covered by relevant Security Council resolutions, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea had linked its cruise missile development to its nuclear weapons programme by referring to the weapons as “strategic” — a term it often used to signify nuclear payload delivery capability.

On 27 May, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea attempted to launch the reconnaissance satellite “Malligyong-1-1” using what it described as a “new-type satellite carrier rocket” from the Sohae Satellite Launching Station. The launch failed due to what state media called “the air blast of the new-type satellite carrier rocket during the first-stage flight”, attributed to reliability issues with a newly developed liquid oxygen and petroleum engine. The country had reportedly conducted tests of a new engine for its satellite carrier rocket before that launch attempt.

Despite plans previously announced by the leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to put three satellites into orbit in 2024, no additional satellite launch attempts were made following the failed effort. This followed three military satellite launches in 2023 — one of them successful — after which Kim Jong Un, General Secretary of the Workers’ Party of Korea, President of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Supreme Commander of the Korean People’s Army, outlined the 2024 satellite plans.

Nuclear activity

The IAEA continued to observe concerning developments in the nuclear programme of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea throughout 2024. The Agency noted indications that the light water reactor at Yongbyon continued to operate intermittently, consistent with an ongoing commissioning process, while the centrifuge enrichment facility at Yongbyon appeared to continue operating. The IAEA also observed indications of the ongoing operation of the 5MW(e) reactor, although it noted that the reactor had been shut down between August and October. The Agency assessed that this period would have provided sufficient time to refuel the reactor and begin its seventh operational cycle.

In February, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea constructed a new annex to the main building in the Kangson complex, significantly expanding the available floor space. In mid-September, the country published photographs of its leader visiting what it described as a “uranium enrichment base”, which appeared to have been taken in the Kangson complex. The IAEA Director General expressed serious concern at this display of an undeclared enrichment facility and Kim Jong Un’s call “to further strengthen the foundation for producing weapon-grade nuclear materials”. The Director General reiterated his call for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to comply fully with its obligations under Security Council resolutions, cooperate promptly with the IAEA in implementing its NPT safeguards agreement and resolve all outstanding issues.

Meanwhile, there were no indications of change at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site, which remained occupied and prepared to support a new nuclear test. Any such test would contravene Security Council resolutions.

Political developments

On 28 March, the Russian Federation vetoed a draft resolution (S/2024/255) that would have extended the mandate of the Panel of Experts responsible for monitoring sanctions implementation under Security Council resolution 1718 (2006), ending the Panel’s operations on 30 April. Initially established under the Committee’s direction by Security Council resolution 1874 (2009), the Panel had its mandate extended most recently through resolution 2680 (2023).

Following the Russian veto, the United States delivered a joint statement on behalf of France, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and itself, asserting that the veto made it more difficult for Member States to address the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s unlawful pursuit of weapons of mass destruction and sanctions evasion efforts within their jurisdictions, thereby jeopardizing international peace and security (S/PV.9591).

In response to the Panel’s termination, 11 countries — Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States — announced on 16 October the establishment of the Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team. In a statement, they said the team would monitor and report violations and evasions of sanctions measures stipulated in relevant Security Council resolutions, assisting in the full implementation of those texts by publishing information based on rigorous inquiry into sanctions violations and evasion attempts.

Bilateral ties between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation continued to strengthen in 2024. On 19 June, the Russian President visited Pyongyang and met Kim Jong Un; the two signed the Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation. The Treaty includes provisions related to mutual defence (article 4) and cooperation in scientific and technological fields, including space, biology, peaceful nuclear energy, artificial intelligence and others (article 10).

The Security Council met four times in 2024 to address the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s ballistic missile launches and military activities (see S/PV.9643, S/PV.9676, S/PV.9775 and S/PV.9820). The Council remained divided, with many members strongly condemning the country’s actions, while China and the Russian Federation attributed rising tensions to the United States and its allies. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, which had begun attending the meetings in July 2023, continued to defend its launches as legitimate self-defence exercises.

The role of verification in advancing nuclear disarmament

In 2024, the Secretary-General submitted for the General Assembly’s seventy-ninth session a compilation of Member States’ views (A/79/93) on the 2023 report of the Group of Governmental Experts to Further Consider Nuclear Disarmament Verification Issues, in line with General Assembly resolution 78/239.

On 24 December, the General Assembly adopted resolution 79/240, requesting the Secretary-General to seek written views from Member States on establishing a group of scientific and technical experts on nuclear disarmament verification within the United Nations. In that regard, it asked the Secretary-General to also account for the views of relevant intergovernmental organizations entrusted with the verification of disarmament or non-proliferation obligations.

The Assembly encouraged Member States to focus their submissions on the possible merits, objectives, mandate and modalities for such a group. It also requested the Secretary-General to convene three in-person informal meetings on the topic, two at United Nations Headquarters in New York, and one at the United Nations Office at Geneva.

In addition, the General Assembly asked the Secretary-General to submit a substantive report at its eightieth session on possible options for establishing a group of scientific and technical experts on nuclear disarmament verification within the United Nations.

International Atomic Energy Agency verification

Since its founding in 1957, the IAEA has served as the focal point for worldwide cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear technology, for promoting global nuclear security and safety and, through its verification activities, for providing assurances that States’ international undertakings to use nuclear material and facilities for peaceful purposes are being honoured. The following is a brief survey of the work of the IAEA in 2024 in the areas of nuclear verification, nuclear security, peaceful uses of nuclear energy and nuclear fuel assurances.

Nuclear verification