Despite the current diplomatic deadlock, the central premise behind [the Conference on Disarmament] remains as vital as ever. The most effective disarmament tool is inclusive diplomacy.We need that diplomacy now — urgently. And you have the power to deliver it, and change this Organization for the better.

Developments and trends, 2024

The year 2024 saw modest progress across the disarmament machinery. In particular, the Conference on Disarmament adopted a decision in June on the work of its 2024 session, a positive signal for the body’s future work that importantly also introduced the concept of continuity between annual sessions. Elsewhere, in the United Nations Disarmament Commission, States began a new three-year cycle by considering two substantive agenda items in their respective working groups: “Recommendations for achieving the objective of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons” in Working Group I; and “Recommendations on common understandings related to emerging technologies in the context of international security” in Working Group II. States welcomed the start of a new cycle and expressed hope in reaching agreement on consensus recommendations.

Overall participation in the General Assembly, First Committee, remained high, with delegates delivering markedly more statements across every issue area than the previous year. In its seventy-ninth session, the Committee adopted five new proposals addressing the effects of nuclear war; the question of nuclear-weapon-free zones; strengthening and institutionalizing the Biological Weapons Convention; weapons of mass destruction in outer space; and artificial intelligence in the military domain. Despite ongoing divisions on matters such as the pace of nuclear disarmament and the ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, the Committee completed its work within the allocated five weeks, adopting a total of 77 draft proposals.

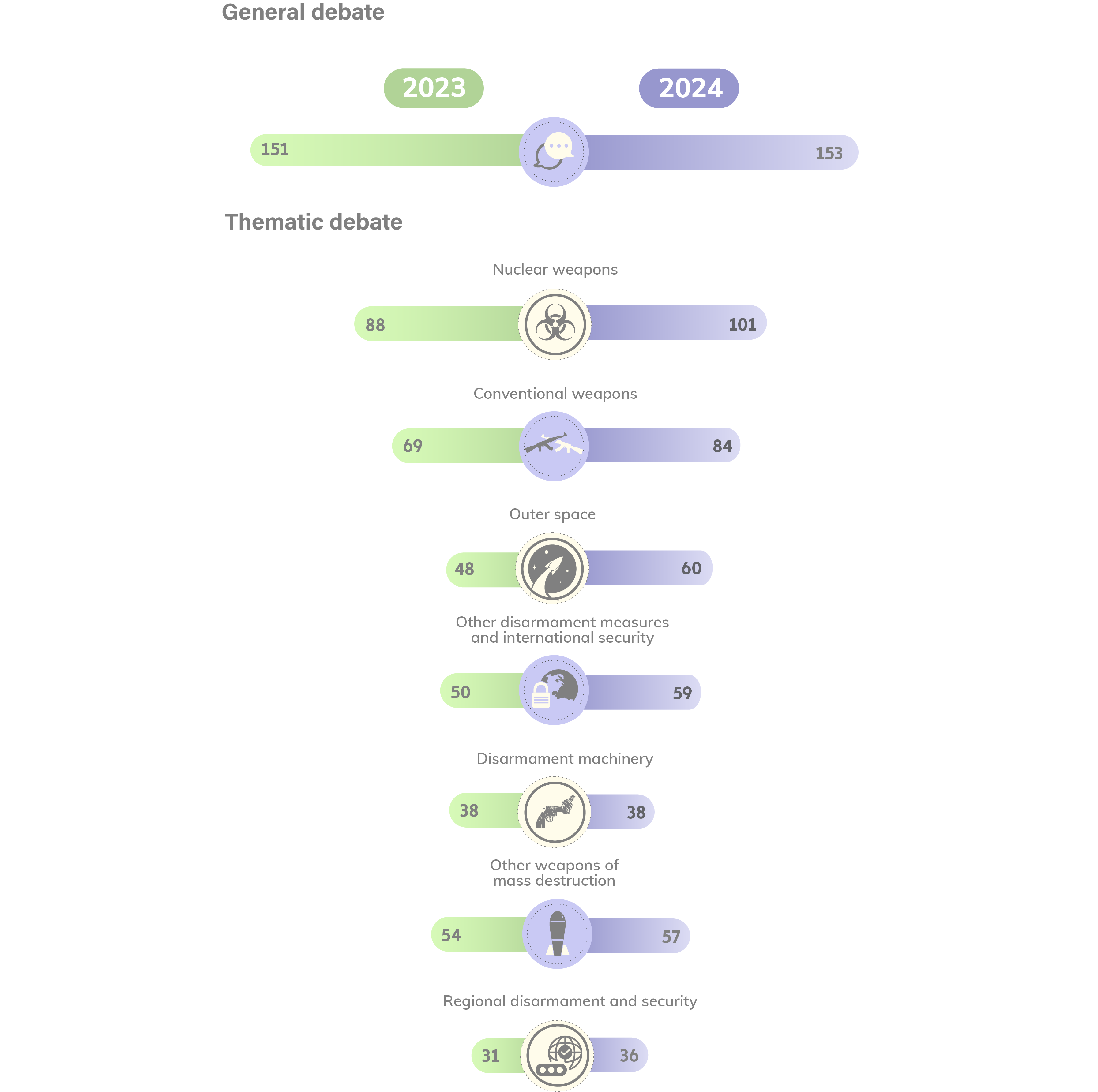

Figure 7. First Committee 2024 at a glance: number of delegations delivering statements, 2023–2024

The rise in delegations delivering statements at the First Committee in 2024 signalled growing global engagement with disarmament and security issues, as more countries voiced concern over nuclear, conventional and outer space threats.

In the Geneva-based Conference on Disarmament, after intensive consultations by the first four Presidents — India, Indonesia, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iraq — the Conference decided to establish five subsidiary bodies for its 2024 session. Each subsidiary body met for one day and held a general exchange of views under the relevant agenda items, touching on specific topics for future meetings. All five bodies agreed on both a report to the Conference and a recommendation that it decide in 2025 to reinstate the subsidiary bodies for that year with their present mandates and coordinators. The issue of participation by States not members of the Conference remained deeply divisive, however; the Conference ultimately opted to consider each request for participation individually, approving 22 of the 39 submitted.[1]

The United Nations Disarmament Commission convened its 2024 substantive session from 1 to 19 April, under the chairmanship of Muhammad Usman Iqbal Jadoon (Pakistan). Immediately after the organizational session, also held on 1 April, the Commission re-elected by acclamation Akaki Dvali (Georgia) as Chair of Working Group I and Julia Elizabeth Rodríguez Acosta (El Salvador) as Chair of Working Group II. The Commission held a general exchange of views over four plenary meetings on 1 and 2 April before the two working groups commenced their work.

The Chair of the 2025 substantive session of the United Nations Disarmament Commission, Muhammad Usman Iqbal Jadoon (Pakistan), addresses the Commission's 390th plenary meeting at United Nations Headquarters, New York, on 1 April. (Credit: UN Photo/Loey Felipe)

In response to the dynamic global environment, the Secretary-General requested the Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters to conduct a strategic foresight exercise over 2024 and 2025 to identify both present and future risks and opportunities for international peace and security emanating from advances in science and technology. The year 2024 marked the midway point in the Board’s discussions, which emphasized a growing need for the United Nations to systematically analyse how scientific and technological advances intersect with disarmament and arms control. Key concerns raised by the Board included ensuring human control over AI and autonomous weapons; ensuring compliance with international law; understanding the roles of various stakeholders, including States, the private sector, civil society, the scientific community and non-State armed groups; and examining how new technologies interact with existing weapon systems. The Board also focused on anticipating the future implications of these developments for disarmament and arms control priorities.

First Committee of the General Assembly

Organization of work

The First Committee of the General Assembly (Disarmament and International Security) held its seventy-ninth substantive session from 7 October to 8 November. Maritza Chan Valverde (Costa Rica) chaired the Committee, becoming the first woman Permanent Representative ever to do so,[2] following her election on 6 June alongside the rest of the session’s Bureau, comprising Rapporteur Pēteris Filipsons (Latvia) and Vice-Chairs El Hadj Lehbib Mohamedou (Mauritania), Abdulrahman Abdulaziz Al-Thani (Qatar) and Vivica Muenkner (Germany).

In an organizational meeting on 3 October, the Committee approved its programme of work as contained in documents A/C.1/79/CRP.1 and A/C.1/79/CRP.2. It then convened 33 in-person meetings, including a joint meeting with the Fourth Committee on possible challenges to space security and sustainability.[3]

For the second consecutive year, the First Committee dedicated one meeting to discussions on programme planning and working methods. At that meeting, held on 17 October, it adopted a draft decision entitled “Information on requests for votes” (L.4), compelling the Chair to provide information, upon request, on States or groups of States requesting votes on proposals as a whole or individual paragraphs.[4] Following a subsequent oral decision to implement the procedure immediately and pursuant to any requests received, the Chair began announcing from the podium which States or groups of States had requested votes on various drafts before Committee action on each cluster of proposals.

The Committee adopted 77 draft proposals — 17 more than in 2023 — and rejected two draft amendments introduced by the Russian Federation. Of the drafts adopted, only 27 texts (25 per cent) were adopted without a recorded vote. Member States requested 150 separate paragraph votes, with several resolutions subject to more than 10 separate paragraph votes each. In total, the Committee voted 201 times during the session, a substantial increase from the 148 votes recorded during the previous session.

The Committee adopted five new proposals at its seventy-ninth session — namely, “Nuclear war effects and scientific research” (L.39); “Comprehensive study of the question of nuclear-weapon-free zones in all its aspects” (L.68); “Strengthening and institutionalizing the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction” (L.73); “Weapons of mass destruction in outer space” (L.7); and “Artificial intelligence in the military domain and its implications for international peace and security” (L.43).

On 18 October, the Committee heard briefings from the Chairs of various disarmament bodies and components of the disarmament machinery and participated in a high-level exchange with the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs. Earlier, on 16 October, the Committee devoted a segment to civil society engagement, hearing from 21 non-governmental organizations on issues spanning the full breadth of its mandate — including nuclear disarmament, conventional weapons control and emerging challenges posed by military applications of artificial intelligence (AI).[5]

The Committee structured its discussions in line with previous sessions, dividing its work into three stages: (a) general debate; (b) discussions on seven thematic clusters (nuclear weapons, other weapons of mass destruction, conventional weapons, regional disarmament and security, outer space (disarmament aspects), other disarmament issues and international security, and disarmament machinery); and (c) action on all draft resolutions and decisions. Nine meetings were dedicated to general debate, followed by 15 meetings for thematic discussions and six meetings for action on all draft resolutions and decisions.

Engagement in the Committee remained strong, with 153 delegations making statements during the general debate segment, two more than the previous year’s total. The thematic debate featured 435 interventions, surpassing the record established in the previous session. While gender balance remained an unrealized goal, with women comprising well below 50 per cent of speakers across all meetings, many delegations welcomed the historic appointment of Ambassador Chan Valverde as Chair and expressed hope that more women would serve in leadership capacities in the future.

The matter of visa issuance by the host country presented an ongoing challenge for the Committee throughout the session. At the organizational meeting on 3 October, the delegation of the Russian Federation said that it would not be able to fully participate in the session due to a lack of visas for several of its members. The delegation asserted that the United States continued to neglect its obligations as the host country. Beyond its general debate statement and occasional points of order, the Russian delegation did not make interventions from the floor, instead directing delegates to its written statements.

The overall atmosphere of the Committee remained contentious, reflecting persistent and deep divisions among Member States. Those divisions were particularly evident in discussions concerning the slow pace of nuclear disarmament, the erosion of strategic nuclear arms control between the United States and the Russian Federation, the war in Gaza and broader Middle East tensions, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and concerns about the expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal. Many States expressed alarm about the deteriorating international security environment, rising military expenditures and growing levels of distrust.

In her opening remarks to the First Committee, the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs noted that 7 October marked one year since the large-scale terror attack against Israel and the subsequent eruption of shocking violence and bloodshed — a stark reminder of what was at stake in the Committee’s work. The High Representative also recalled that the Committee was meeting after the Summit of the Future, where States had adopted the Pact for the Future (resolution 79/1), alongside the Global Digital Compact and the Declaration on Future Generations (resolution 79/1, annexes I and II). The Summit, she emphasized, had highlighted challenges to international peace and security, including ongoing violations of the Charter of the United Nations and international humanitarian law. The High Representative further lamented that nuclear posturing had re-entered the discourse and that the emergence of new domains of potential conflict was no longer an abstract concern.

On 8 October, the President of the seventy-ninth session of the General Assembly, Philémon Yang (Cameroon), addressed the Committee, emphasizing that nuclear-weapon States must take the lead in preventing nuclear war and fulfilling their commitments under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The President further underscored that States must remain vigilant regarding scientific advancements and the potential misuse of biological and chemical weapons, while also urgently confronting the challenges posed by emerging technologies, including lethal autonomous weapons and malicious cyber activities. He highlighted the threats to civilians from the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, as well as from small arms and light weapons, cluster munitions and landmines. The President also noted with concern that global military expenditures had reached record levels, diverting vital resources from essential sectors such as the economy and education.

In line with past practice, throughout the thematic debate, the Committee heard briefings from the Chairs of ongoing and recently concluded disarmament bodies and experts groups, including on 23 October from Maritza Chan Valverde (Costa Rica), President of the fourth United Nations Conference to Review Progress Made in the Implementation of the Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects; on 25 October from Burhan Gafoor (Singapore), Chair of the Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies 2021–2025; and on 29 October from Bassem Hassan (Egypt), Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space.

On 28 October, the Committee received briefings from the Directors of the regional centres of the Office for Disarmament Affairs for Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia and the Pacific. These were followed by the traditional panel on disarmament machinery, which included the President of the Conference on Disarmament, Daniel Meron (Israel); the Chair of the Disarmament Commission, Muhammad Usman Iqbal Jadoon (Pakistan); the Chair of the Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters, Shorna-Kay Richards (Jamaica); and the Director of the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR).

On 18 October, at its twelfth meeting, the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs engaged in an annual exchange with the First Committee, joining high-level officials in the field of arms control and disarmament nominated by the General Assembly regional groups. In her address, the High Representative reflected on themes from the general debate, particularly the widespread concerns of States about the deteriorating international security environment, declining compliance with disarmament obligations, and rising military expenditures. She emphasized the First Committee’s pivotal role as a platform for engaging diverse stakeholders, including civil society and academia. The High Representative also underscored the importance of investing in disarmament education, highlighting the Disarmament Education Strategy of the Office for Disarmament Affairs. She emphasized that existential threats to the planet — including the continued existence of nuclear weapons, the climate crisis and increasing inequality and injustices — must be addressed through intergenerational, cross-cultural, cross-sectoral and cross-regional action.

Also on the panel were Martha Mariana Mendoza Basulto, who represented the Secretary-General of the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL), nominated by the Group of Latin America and the Caribbean; and Robert in den Bosch (Kingdom of the Netherlands), Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems, nominated by Western European and other States.

Speaking on behalf of OPANAL, the representative highlighted several activities, including a joint declaration commemorating the International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons, on 26 September, and a working paper submitted to the second session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 NPT Review Conference (NPT/CONF.2026/PC.II/WP.14). The organization expressed support for undertaking a new comprehensive study on nuclear-weapon-free zones to facilitate the potential establishment of new zones and highlighted its member States’ efforts to promote women’s inclusion and gender mainstreaming in disarmament discussions.

The Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems briefed delegates on the Group’s progress. Established in 2016 by the High Contracting Parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, the Group conducted numerous informal consultations throughout 2024 to refine key considerations, including the definition of lethal autonomous weapons systems. The Chair concluded by expressing optimism about the progress achieved by the Group, despite difficult international security circumstances.

On 2 December, the General Assembly acted on 72 of the 77 draft resolutions and decisions on substantive items approved by the First Committee. The Assembly did not act on five texts due to pending review of their programme budget implications by the Fifth Committee: “Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies 2021–2025 established pursuant to General Assembly resolution 75/240” (A/79/403; formerly L.13); “Nuclear war effects and scientific research” (A/79/408, draft resolution XVII; formerly L.39); “Artificial intelligence in the military domain and its implications for international peace and security” (A/79/408, draft resolution XX; formerly L.43); “Group of Scientific and Technical Experts on Nuclear Disarmament Verification” (A/79/408, draft resolution XXXVI; formerly L.67); and “Comprehensive study of the question of nuclear-weapon-free zones in all its aspects” (A/79/408, draft resolution XXXVII; formerly L.68/Rev.1). In presenting the reports of the First Committee, the Rapporteur, Pēteris Filipsons (Latvia), noted that the Committee required two additional plenary meetings beyond those originally scheduled to complete its work on time.

On 24 December, the General Assembly adopted the outstanding proposals: “Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies 2021–2025 established pursuant to General Assembly resolution 75/240” (79/237); “Artificial intelligence in the military domain and its implications for international peace and security” (79/239), “Group of Scientific and Technical Experts on Nuclear Disarmament Verification” (79/240), “Comprehensive study of the question of nuclear-weapon-free zones in all its aspects” (79/241) and “Nuclear war effects and scientific research” (79/238). In addition, the draft decision “Open-ended working group on the prevention of an arms race in outer space in all its aspects” was adopted as decision 79/512 without a vote.

Exchange with civil society and meeting on working methods and programme planning

On 17 October, at its eleventh meeting, the First Committee held a debate on working methods and programme planning, in accordance with General Assembly resolution 78/244 and the Committee’s adopted programme of work and timetable (A/C.1/79/CRP.1). To facilitate productive discussions, the Chair circulated a non-paper in advance containing guiding questions on matters such as time management, transparency and informal consultations, civil society participation, inclusion and gender parity, and the possibility of the biennialization or triennialization of resolutions. The Committee heard interventions from 19 States, four of which spoke on behalf of a group of States.[6]

Also at its eleventh meeting, in line with the decision from its organizational session, the Committee took action on the draft decision “Information on requests for votes” (L.4), adopting it without a vote. Several interventions during the meeting served as explanations of vote on this draft decision. Following adoption and a subsequent oral decision to apply the modalities immediately, the Chair announced that she would provide information on vote requests from the podium throughout the current session. In its earlier introduction of the draft decision, Singapore, speaking also on behalf of South Africa, recalled the existing First Committee practice of maintaining anonymity for States requesting votes on draft proposals or individual paragraphs. The co-sponsors emphasized that their intention was not to infringe on any State’s right to request a vote, but rather to enhance procedural transparency.[7]

In their deliberations on programme planning, delegates expressed regret that the Committee for Programme and Coordination had again failed to reach consensus on conclusions and recommendations on programme 3, Disarmament, in the proposed programme plan for 2025 (A/79/6 (Sect. 4), part A). While one delegation emphasized that programme planning should remain depoliticized, a group of States stressed that it must continue as a consensus-based process, noting that the Fifth Committee holds final responsibility for adopting the programme plan and budget. Another delegation asserted that the meeting on 17 October duplicated the Fifth Committee’s work, stating it would have preferred the First Committee not to address the matter. Separately, a group of States requested that the Chair propose to the Fifth Committee that the General Assembly adopt the proposed programme plan without modification.

Several delegations provided detailed input on the First Committee’s working methods, including by addressing specific points from the Chair’s non-paper. Some called for more comprehensive consideration of potential reforms beyond the newly adopted measure on vote request transparency. One delegation observed that working methods cannot be standardized across all forums of the disarmament machinery, given the unique requirements of each one, while another emphasized the intrinsic connections among those bodies and urged enhanced coordination among them.

Multiple delegations noted the substantial workload of the First Committee during its five scheduled weeks, with some expressing openness to allocating additional meetings. In particular, several emphasized the need for more time to consider draft proposals. Other priorities included the critical importance of multilingualism, with delegations stressing the necessity of providing interpretation of every mandated meeting in all six United Nations official languages and the timely dissemination of Committee documents in all those languages. Several interventions emphasized the fundamental principle of equal participation of all States, noting the importance of timely visa issuance to ensure all delegation members could attend.

Joint panel discussion of the First and Fourth Committees

By General Assembly resolutions 78/52 of 4 December 2023 and 78/72 of 7 December 2023, the First Committee convened a joint half-day panel with the Special Political and Decolonization Committee (Fourth Committee) on 30 October to address possible challenges to space security and sustainability. A draft programme was prepared by the Office for Disarmament Affairs and the Office for Outer Space Affairs (A/C.1/79/CRP.5; A/C.4/79/CRP.1) and circulated for information.

The Chairs of the First and Fourth Committees opened the plenary meeting. Following remarks by the Director and Deputy to the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs and by the Director of the Office for Outer Space Affairs, both Committees heard presentations from invited panellists, which included the Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space, Bassem Hassan (Egypt); the Chair of the Disarmament Commission, Muhammad Usman Iqbal Jadoon (Pakistan); the current and incoming Chairs of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Sherif Sedky (Egypt) and Rafiq Akram (Morocco); the former Chair of the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, Manuel Metz of the German Aerospace Center; and a contributor to the negotiations on the outer space elements included in the Pact for the Future, Ana Avila (Costa Rica).

The Committees heard statements on outer space from delegations of 12 Member States — speaking both in their national capacities and on behalf of a group,[8] and one observer organization.[9] Member States highlighted the value of the joint panel discussion for ensuring complementarity and dialogue among various United Nations bodies, particularly since different aspects of outer space were typically addressed in separate forums.

Concerns about heightened threats and risks in outer space were voiced by multiple delegations, who noted that the domain was becoming increasingly contested and congested. They cited specific challenges, including the exponential growth of object launches, proliferation of space debris and destructive anti-satellite weapon tests. Some delegations voiced specific concern regarding the possible placement of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in orbit. A number of Member States rejected the placement of any type of weapon in space and expressed alarm about risks associated with dual-use technologies that could exacerbate tensions among space actors. Concern was also expressed that certain national space programmes were transforming space into another domain of conflict.

In that context, Member States expressed broad support for developing and implementing transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space activities, with several calling for the negotiation of a legally binding instrument on the prevention of an arms race in outer space. Some States also recognized the value of non-binding measures to address threats relating to space systems. In that regard, discussions on norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviour featured prominently. While some delegations emphasized that such voluntary approaches should not substitute for legally binding commitments, others noted their potential as buildings blocks for a legally binding instrument.

The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space also received strong support from delegations, with calls for enhanced resources to bolster its work. Several representatives identified the Committee as the optimal forum for addressing space traffic management concerns. The Committee’s Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines were welcomed by many delegations, who urged their prompt implementation. Meanwhile, several States expressed appreciation for a gender mainstreaming toolkit created by the Office for Outer Space Affairs, and some noted with interest a proposal for a consultative mechanism for lunar activities (A/AC.105/C.2/2024/CRP.18/Rev.1), which promised to foster increased discussions, coordination and cooperation for cislunar and lunar activities.

A number of delegations expressed support for involving non-State stakeholders in multilateral deliberations on the prevention of an arms race in outer space. While one view highlighted the potential positive contributions of commercial actors towards sustainable development, another emphasized that all parties operating in outer space, including commercial actors, should conduct their activities responsibly. The issue of satellite mega-constellations in low-Earth orbit prompted various delegations to suggest collaborative approaches among all States to prevent long-term impacts on space sustainability.

Overview of key substantive issues

Nuclear weapons

The Committee took action on 25 resolutions and decisions related to nuclear weapons, adopting only three by consensus. Those consensus resolutions all addressed nuclear-weapon-free zones: “African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty” (79/15), “Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia” (79/24) and “Mongolia’s international security and nuclear-weapon-free status” (79/30).

Notable among the resolutions adopted by vote were those mandating new studies: “Nuclear war effects and scientific research” (79/238), mandating further research on the effects of nuclear war; and “Comprehensive study of the question of nuclear-weapon-free zones in all its aspects” (79/241), updating previous work on nuclear-weapon-free zones.

Throughout the general debate and thematic discussions, the deep divisions between nuclear-weapon States and non-nuclear-weapon States remained evident. Non-nuclear-weapon States decried ongoing nuclear modernization programmes, resurgent arms race dynamics and the growing prominence of nuclear weapons in the security doctrines of nuclear-weapon States and their allies. Meanwhile, nuclear-weapon States maintained their position that nuclear disarmament efforts must account for the current security environment, advocating for what they characterized as a pragmatic approach.

Some nuclear-weapon States notably opposed resolutions such as “Addressing the legacy of nuclear weapons: providing victim assistance and environmental remediation to Member States affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons” (79/60), as well as “Nuclear war effects and scientific research” (79/238), which mandates the first United Nations study on nuclear war effects since 1989. Nuclear-sharing agreements also generated significant debate, with increased criticism of those policies prompting lengthy defences by Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Kingdom of the Netherlands — current hosts of United States nuclear weapons. Separately, many non-nuclear-weapon States expressed concern to distinguish certain groups of countries beyond the NPT’s two recognized categories of “nuclear-weapon States” and “non-nuclear-weapon States”, viewing such characterizations as potentially undermining the Treaty’s fundamental structure.

Other weapons of mass destruction

The Committee adopted six resolutions under this cluster, including a new resolution introduced by Kazakhstan, Kiribati and Saudi Arabia on strengthening and institutionalizing the Biological Weapons Convention. This resolution, entitled “Strengthening and institutionalizing the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction” (79/79), garnered consensus.

The resolution “Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction” (79/56) was adopted by vote for an eleventh consecutive year. The need for a vote in the seventy-ninth session stemmed from contentious language regarding the possession and use of chemical weapons by the Syrian Arab Republic.

During the general debate and thematic discussions, numerous States expressed their appreciation for the completion in 2023 of the verified destruction of all declared chemical-weapon stockpiles by States parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. At the same time, they emphasized that support for the Convention must continue in view of persistent challenges, particularly those related to non-State actors and emerging technologies. Many delegations expressed concern about two new issues with the Syrian Arab Republic’s declaration identified in August by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Another prominent issue raised by several States was the alleged use of chemical weapons in the conflict in Ukraine. Ukraine specifically condemned the Russian Federation’s use of riot control agents and alleged Russian disinformation campaigns targeting peaceful biological activities conducted by the United States in Ukraine.

Regarding biological weapons, the Committee adopted by consensus its annual resolution on the Biological Weapons Convention (79/78), maintaining its established practice. Numerous Member States welcomed the success of the ninth Review Conference and the establishment of the Working Group on the Strengthening of the Convention. The Working Group presented a unique opportunity to revitalize the Convention, according to multiple States, whose delegations welcomed progress both on establishing international cooperation and assistance mechanisms, and on monitoring scientific and technological developments. Several States underscored the importance of science and technology reviews in strengthening the Convention, calling for further efforts to enhance the implementation of article X.

Outer space (disarmament aspects)

The Committee acted on six resolutions and one decision under this cluster, adopting two annual resolutions without a vote: “Prevention of an arms race in outer space” (79/19) and “Transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space activities” (79/51).

A decision entitled “Open-ended working group on the prevention of an arms race in outer space in all its aspects” (79/512) was adopted by vote with the vast majority of States voting in favour. This decision marked a significant development, resulting in the convergence of two previously separate open-ended working groups on outer space security established in the previous General Assembly session by resolutions 78/20 and 78/238. The convergence was championed by a cross-regional group of States, led by Egypt, aiming to establish a single platform to comprehensively address questions related to the prevention of an arms race in outer space. This unified approach would encompass both the consideration of norms, rules and principles, and the pursuit of legally binding measures. Through intensive consultations with the main sponsors of the two previously established working groups — the Russian Federation and the United Kingdom — Egypt successfully facilitated the merger of these initiatives, garnering overwhelming support from Member States.

Under this cluster, the United States introduced a new resolution entitled “Weapons of mass destruction in outer space” (79/18), which was adopted by a wide majority of States. The Russian Federation proposed two amendments to the text (L.78/Rev.1 and L.79/Rev.1), arguing that the draft lacked practical elements and failed to adequately emphasize issues regarding the “placement” of weapons and the pursuit of legally binding measures. The Russian delegation further contended that the resolution should be expanded to cover all types of weapons, not just weapons of mass destruction. The co-sponsors of the resolution opposed the draft amendments, characterizing them as “hostile” and asserting that they would fundamentally alter the scope of the resolution and were not legally sound. The Committee ultimately rejected both proposals.

Conventional weapons

The Committee adopted 10 resolutions under this cluster, including annual resolutions dedicated to established treaties, such as the Convention on Cluster Munitions, the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (79/34), the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects (79/75) and the Arms Trade Treaty (79/52). The biennial resolution “Countering the threat posed by improvised explosive devices” (79/53), introduced by Australia, France and Nigeria, was adopted as a whole without a vote, although several paragraph votes were taken, including on elements related to gender.

Throughout the general debate and thematic cluster discussions, States devoted considerable attention to the need for capacity-building in small arms and light weapons control and conventional ammunition management. Many delegations welcomed two recent developments: the adoption of the Global Framework for Through-life Conventional Ammunition Management (A/78/111, annex) and the successful conclusion of the fourth Review Conference of the Programme of Action on Small Arms and Light Weapons. A second iteration of the resolution addressing the Global Framework (79/54) was adopted by a vote, with the vast majority of States voting in favour. The resolution specified that the first Preparatory Meeting of States would be convened from 23 to 27 June 2025.

The annual resolution “The illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects” (79/40), led by South Africa, was adopted as a whole without a vote. The resolution contained several forward-looking elements, including mandating a fifth Review Conference of the Programme of Action in 2030 and scheduling biennial meetings of States in 2026 and 2028. In response to evolving challenges, the resolution established an open-ended technical expert group to address developments in manufacturing, technology and design of small arms and light weapons. Additionally, the resolution requested that the Secretariat undertake two specific tasks within existing resources: establish a structured procedure to facilitate matching assistance needs with available resources, and conduct a study on obliterated markings and methods for marking recovery.

Other disarmament measures and international security

The Committee adopted 13 resolutions and one decision under this cluster, including one on information and communications technologies security. Despite concerns that competing resolutions on the issue of information and communications technologies security might emerge, as had occurred in previous years, the Committee adopted a single, consensus resolution entitled “Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies 2021–2025 established pursuant to General Assembly resolution 75/240” (79/237). The resolution, sponsored by Singapore in its capacity as Chair of the Open-ended Working Group, endorsed the Working Group’s latest progress report (A/79/214, annex), recalled the consensus elements reached on the establishment of a future permanent mechanism on these matters beyond 2025, and mandated additional intersessional meetings.

Throughout the Committee, many States welcomed the work of the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems, under the auspices of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. Led by Austria, a second iteration of the resolution “Lethal autonomous weapons systems” (79/62) was adopted by a large majority of States, but also subject to many individual paragraph votes. The resolution called for informal consultations on the topic in 2025 to consider the report of the Secretary-General issued on the topic (A/79/88), in full complementarity with and in a manner that supports the fulfilment of the mandate of the Group of Governmental Experts.

States regularly raised the issue of AI applications in the military domain. A new resolution on this topic was adopted (79/239), acknowledging the potential international peace and security implications of these applications and requesting a report from the Secretary-General with a specific focus on areas other than lethal autonomous weapons systems.

Regarding gender and diversity, the Committee continued to hear a growing number of calls for the inclusion of more diverse voices, including those of women. The biennial resolution on “Women, disarmament, non-proliferation and arms control”, led by Trinidad and Tobago, was adopted as a whole by consensus, although it was subject to 12 paragraph votes, a record. The updated version of the resolution notably acknowledged, for the first time, women’s contribution in all aspects of arms control and disarmament efforts, including those related to weapons of mass destruction.

Disarmament machinery

The Committee adopted nine resolutions under this cluster, including the annual texts dedicated to the United Nations regional centres for peace and disarmament (79/65, 79/66, 79/67 and 79/70). The annual resolutions on the reports of the Conference on Disarmament and the Disarmament Commission (79/71 and 79/72) were adopted without a vote.

While States continued to lament the lack of substantive negotiations in the Conference on Disarmament, many welcomed the decision allowing the establishment of subsidiary bodies during the 2024 session. States also expressed appreciation for the Disarmament Commission’s ongoing consideration of emerging technologies in the context of international security. On the matter of the possible convening of the fourth special session of the General Assembly devoted to disarmament, the annual resolution presented by States of the Non-Aligned Movement was adopted by consensus (79/44).

United Nations Disarmament Commission

The United Nations Disarmament Commission convened its 2024 substantive session from 1 to 19 April at United Nations Headquarters, with Muhammad Usman Iqbal Jadoon (Pakistan) serving as Chair. The session marked the beginning of a new three-year cycle of deliberations, with the Commission taking up two agenda items: (a) recommendations for achieving the objective of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons (item 4); and (b) recommendations on common understandings related to emerging technologies in the context of international security (item 5).

At its organizational session on 1 April (A/CN.10/PV.390), the Commission elected its Chair and the following Vice-Chairs by acclamation: Amr Essameldin Sadek Ahmed (Egypt), Mohammed Lawal Mahmud (Nigeria) and Viviana Sanabria Duarte (Paraguay). Katherine Sarah Jones (United Kingdom) was elected as an additional Vice-Chair the following day. Ms. Sanabria Duarte agreed to serve as Rapporteur. At the opening of the substantive session (A/CN.10/PV.391), held immediately after the organizational session, the Commission re-elected, by acclamation, Akaki Dvali (Georgia) as Chair of Working Group I, and Julia Rodríguez Acosta (El Salvador) as Chair of Working Group II.

Speaking as the substantive session got under way, the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs underscored the Commission’s importance amid heightened global tensions and increased strategic arms competition, combined with decreasing trust between nuclear-weapon States. With respect to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, she suggested that the Commission focus on providing further accountability for the existing commitments of NPT States parties; developing transparency, confidence-building and crisis-communication measures to prevent nuclear-weapon use; fostering constructive engagement between critics and supporters of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons; and accelerating efforts towards the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. On emerging technologies, she encouraged the Commission to identify gaps in current multilateral discussions by examining convergences in areas such as AI and biotechnology, alongside the interplay of various technological advancements with governance frameworks affecting international security.

The Commission held a general exchange of views for almost four plenary meetings on 1 and 2 April (A/CN.10/PV.391–A/CN.10/PV.394), before the two working groups commenced their work. A total of 76 statements were delivered by Member States and observers[10] — almost the same number as in 2023. Most States focused on nuclear-related issues in their statements, rather than on emerging technologies.

Following three weeks of deliberations in plenary meetings and its respective working groups, the Disarmament Commission concluded its 2024 substantive session at its 396th meeting, on 19 April, by adopting a final report, with the consensus reports of its two working groups, which provided a procedural summary for submission to the General Assembly at its seventy-ninth session (A/79/42). No recommendations were put forward on the agenda items (A/CN.10/PV.396).

Working Group I

Working Group I based its discussions on agenda item 4, “Recommendations for achieving the objective of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons”, continuing its deliberations on the same agenda item from previous cycles. At its first meeting, on 3 April, upon the Chair’s suggestion, delegations agreed to use the Chair’s paper from the previous three-year cycle, dated 19 April 2023 (A/CN.10/2023/WG.I/CRP.1/Rev.2), as a starting point for their work in the new session.

Following robust exchanges of views and various proposals from Member States between the second and seventh meetings, the Chair subsequently revised and circulated updated papers on 5, 9, 16 and 19 April. At the eighth and final meeting of the year’s session, on 19 April, delegations expressed their initial positions and reflections on the Chair’s revised paper (A/CN.10/2024/WG.I/CRP.1/Rev.2), which was issued under the Chair’s own responsibility and without prejudice to the position of delegations. At the same meeting, the Working Group considered and adopted its report on the agenda item by consensus (A/79/42, para. 20).

Working Group II

Working Group II conducted deliberations on agenda item 5, “Recommendations on common understandings related to emerging technologies in the context of international security”. The Group organized its work using the framework provided in the Secretary-General’s 2023 report on current developments in science and technology and their potential impact on international security and disarmament efforts (A/78/268). Following the structure of section II of the report, the Working Group examined various emerging technologies through expert presentations and substantive exchanges among delegations.

To inform its deliberations and avoid duplication of efforts, the Working Group received briefings from Chairs of United Nations processes addressing emerging technologies in international security contexts. Member States also delivered presentations on relevant State-led initiatives. Throughout its meetings, the Group conducted an exchange of views on both the potential benefits and risks of emerging technologies in the context of international security.

The Working Group began its work on 3 April with a general exchange of views on agenda item 5. At its second meeting, on 4 April, representatives from the Office for Disarmament Affairs presented the Secretary-General’s report (A/78/268), followed by an initial exchange of views among delegations. The Group then conducted a series of thematic discussions over the course of five meetings from 5 to 12 April:

- 5 April: Artificial intelligence and autonomous and uncrewed systems (section II.A)

- 8 April: Digital technologies (section II.B)

- 9 April: Biology and chemistry (section II.C)

- 11 April: Space and aerospace technologies (section II.D)

- 12 April: Electromagnetic technologies (section II.E) and materials technologies (section II.F).

During those thematic discussions, the Working Group benefited from presentations by representatives of international organizations and non-governmental entities.[11]

At its eighth meeting, on 15 April, the Working Group heard and exchanged views on presentations by the Chair of the Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies 2021–2025, Burhan Gafoor (Singapore); the Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems, Robert in den Bosch (Kingdom of the Netherlands); and the Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space, Bassem Hassan (Egypt).

At the same meeting, the Working Group heard presentations on State-led initiatives related to emerging technologies from representatives of Austria, China, the Republic of Korea and the United States.

At its ninth meeting, on 16 April, the Group held a wide-ranging exchange of views on emerging technologies in the context of international security. The Working Group concluded its substantive deliberations at the tenth meeting, on 18 April, discussing the outcome of its work.

Based on those discussions, the Chair issued a summary reflecting her understanding of the key points raised without prejudice to the position of any delegation. The summary was intended to support States in their further consideration of the agenda item during the subsequent two annual sessions of the present three-year cycle. At its tenth meeting, the Working Group concluded its work with the consensus adoption of a procedural report (A/79/42, para. 21).

Conference on Disarmament

The Conference on Disarmament held part I of its 2024 session from 22 January to 28 March (CD/PV.1695–CD/PV.1715); part II from 13 May to 28 June (CD/PV.1716–CD/PV.1730); and part III from 29 July to 13 September (CD/PV.1731–CD/PV.1736). The session comprised 42 formal plenary meetings and six informal plenary meetings.

Adoption of the agenda

The 2024 session opened on 23 January under the presidency of Anupam Ray (India). As in previous years, the Conference adopted its agenda at its first meeting (CD/2382).

At the time of adoption, the President acknowledged a formal proposal by Pakistan to include a new agenda item entitled “New technologies: the development, deployment, integration and use of AI for military purposes, and autonomous weapon systems” (CD/2334, annex). Noting the absence of consensus on this proposal, the President indicated that the matter would remain open for further consideration throughout the 2024 session.

Several member States of the Conference expressed the view that discussions on AI in the military domain could be accommodated within the Conference’s existing agenda items. These delegations suggested various approaches, with some preferring to address the issue under agenda item 5, “New types of weapons of mass destruction and new systems of such weapons; radiological weapons”, whereas others advocated for its inclusion under item 6, “Comprehensive programme of disarmament”.

Requests for participation by States not members of the Conference

In a significant development from the previous year, the Conference addressed the issue of observer participation that had remained unresolved throughout 2023. By the opening of the 2024 session, 33 States not members had submitted requests to participate in the work of the Conference (CD/WP.653).

The matter was not resolved at the first plenary meeting owing to persistent disagreement over the procedure, specifically whether to address all requests through a single comprehensive decision or to consider each request individually. Following discussions on 30 January, the Conference reached a procedural compromise on 1 February, deciding to consider each request individually in their chronological order of receipt by the Secretariat.

Over the course of the session, the Conference considered and took action on 39 requests from non-member States of the Conference to participate in its work, accepting 22 requests and rejecting 17 (CD/PV.1698, CD/PV.1699, CD/PV.1710).

High-level segment

The Conference held its high-level segment from 26 to 28 February under the presidency of Febrian Ruddyard (Indonesia) (CD/PV.1703–CD/PV.1707). The segment attracted substantial participation, with dignitaries representing 49 States delivering in-person statements and an additional 10 submitting pre-recorded video messages. The speakers included the Secretary-General of the United Nations and the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization.

Complementing the formal proceedings, the presidency, with support from the Secretariat, organized two informal thematic discussions on 27 February. The first discussion, “Overcoming stagnation: ensuring the improved and effective functioning of the Conference on Disarmament” was moderated by Camille Petit (France). The second, “Addressing contemporary challenges: the promotion of measures to reduce distrust and build confidence”, was moderated by the President himself. Indonesia subsequently circulated a Chair’s summary prepared by the Secretariat (CD/WP.654).

Decisions on the work of the Conference for 2024

Efforts towards a programme of work continued to present challenges for the Conference. In accordance with past decisions, consultations on a draft programme had been initiated the previous year by India as the first President-designate for the 2024 session. Those consultations extended into the next session, using as their basis the decision on the work of the Conference negotiated in 2022 under China’s presidency and later adopted under the presidency of Colombia (CD/2229).

On 7 February, the Conference held a plenary meeting on an informal draft decision circulated by India’s presidency. Despite continued consultations with various delegations to narrow differences, the President, Anupam Ray (India), concluded on 16 February that consensus remained elusive. The matter was subsequently transferred to the incoming presidency of Indonesia.

Under the presidency of Indonesia, consultations continued based on the latest draft developed under India’s presidency. Its approach transitioned from bilateral consultations held before the high-level segment, to group discussions conducted thereafter. Setting a clear deadline, the second President, Febrian Ruddyard (Indonesia), announced that if consensus could not be achieved by 4 March, Indonesia would redirect the remainder of its presidency to convening thematic plenary meetings on substantive issues within the Conference’s purview.

The third President of the 2024 session, Ali Bahreini (Islamic Republic of Iran), continued bilateral consultations on a draft decision on the work of the Conference, also based on the last draft text developed under the first presidency. On 20 May, the President circulated a working paper entitled “On the dual-track approach to the work of the Conference on Disarmament” (CD/WP.655), describing the efforts undertaken by the Iranian presidency and putting forward a proposal for a draft decision. France and the United States circulated a working paper containing comments on the President’s draft (CD/WP.656), and the Conference discussed the proposal on 21 May.

The fourth President of the Conference, Abdul-Karim Hashim Mostafa (Iraq), continued consultations both bilaterally and in a small-group format, working from the draft proposal of the third President and with support from the Secretariat. These consultations successfully resolved the outstanding issues on the text, which had included questions on how to refer to the past work of the Conference and how to reflect the goal of ensuring continuity across its annual sessions.

In a significant milestone, the Conference adopted a decision on 13 June to establish five subsidiary bodies: four of them respectively covering agenda items 1–4, and a fifth covering agenda items 5, 6 and 7, to meet during the 2024 session (CD/2390). This achievement was complemented on 19 June by a second decision appointing coordinators for the subsidiary bodies and establishing a timetable for their meetings (CD/2391). Following those decisions, the fourth and fifth Presidents convened an informal preparatory meeting of the coordinators to harmonize their approach towards organizing the subsidiary bodies.

On 24 June, at the request of the Russian Federation, the fifth President of the Conference, Noel White (Ireland), convened a plenary meeting to provide the coordinators an opportunity to outline their respective plans (CD/PV.1730). The coordinators each anticipated facilitating a general exchange of views, including on specific issues that the Conference could address at its 2025 session. Each subsidiary body would then consider a technical report containing any recommendations for continuing the substantive work of the Conference in 2025.

Work of the subsidiary bodies

Following the adoption of the decisions establishing the subsidiary bodies and appointing their coordinators, each body convened as follows:

- Subsidiary Body 1 (Cessation of the nuclear arms race and nuclear disarmament) met on 25 June

- Subsidiary Body 2 (Prevention of nuclear war, including all related matters) met on 28 June

- Subsidiary Body 3 (Prevention of an arms race in outer space) met on 6 August

- Subsidiary Body 4 (Effective international arrangements to assure non-nuclear-weapon States against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons) met on 8 August

- Subsidiary Body 5 (New types of weapons of mass destruction and new systems of such weapons; radiological weapons/Comprehensive programme of disarmament/Transparency in armaments) met on 13 August.

Each subsidiary body conducted a general exchange of views under its respective agenda items, including discussions on specific topics that could be considered at its future meetings.

In advance of the meetings of the subsidiary bodies, the fifth President circulated a non-paper, prepared by the Secretariat, which provided a common template for the technical reports of the subsidiary bodies, including recommendations for continuing work in 2025. During the meeting of Subsidiary Body 1, States discussed amendments to the template and negotiated the report of the subsidiary body. Subsequently, all the subsidiary bodies agreed to their reports based on the agreed template.

Each subsidiary body recommended in its respective report to the Conference that, for its 2025 work decision and in accordance with the rules of procedure, the subsidiary bodies should resume their work in 2025 with their present mandates as specified in decision CD/2390. They further recommended that the coordinators, appointed pursuant to decision CD/2391, be reappointed for 2025. Additionally, each subsidiary body encouraged its respective coordinator, under the President’s authority and to ensure an inclusive, balanced and fair approach, to continue conducting informal consultations on both organizational and substantive aspects of its possible future work, consistent with the rules of procedure.

On 15 August, the Conference adopted all five subsidiary body reports as submitted by the fifth President (CD/2392, CD/2393, CD/2394, CD/2395 and CD/2396).

Other substantive work of the Conference in 2024

From mid-March until the establishment of the subsidiary bodies in June, the Conference resumed its previous session’s practice of holding thematic plenary meetings based on proposals by the presidency. These meetings addressed various agenda items, as follows:

- 12 March: Fissile material cut-off treaty (item 2, “Prevention of nuclear war, including all related matters”)

- 14 March: Negative security assurances (item 4)

- 21 March: Nuclear disarmament verification (item 1, “Cessation of the nuclear arms race and nuclear disarmament”), with a panel featuring former staff of the International Atomic Energy Agency and UNIDIR

- 28 March: Prevention of an arms race in outer space (item 3), with a panel featuring the Chair of the Group of Governmental Experts on Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space, as well as representatives of UNIDIR and the Office for Disarmament Affairs

- 14 May: Relationship between disarmament and development (item 6, “Comprehensive programme of disarmament”), with a panel featuring the Office for Disarmament Affairs and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- 23 May: Zones free of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction (item 2, “Prevention of nuclear war, including all related matters”), with a panel featuring the President of the fourth session of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction, Taher El-Sonni (Libya), as well as UNIDIR and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- 28 May: Cessation of the nuclear arms race and nuclear disarmament (item 1)

- 30 May: Promoting transparency on nuclear doctrines and arsenals (item 7, “Transparency in armaments”), held as an informal meeting with a panel featuring UNIDIR, the Federation of American Scientists and King’s College London

- 6 June: Building capacity in disarmament through education and research (item 6, “Comprehensive programme of disarmament”), with a panel featuring Tomiko Ichikawa (Japan), the Office for Disarmament Affairs and UNIDIR

- 11 June: Challenges of new and emerging threats: assessing the impact of emerging technologies on international security and arms control efforts (item 6, “Comprehensive programme of disarmament”), with a panel featuring representatives from France, the Republic of Korea and the United States

Consideration and adoption of the report to the General Assembly

The sixth President of the Conference, Meirav Eilon Shahar (Israel), facilitated negotiations on the consideration and adoption of the Conference’s annual report to the General Assembly. His efforts, which built upon the successful model established by Hungary in 2023, resulted in the adoption of a comprehensive procedural report (CD/2430). Israel also led consultations on the annual draft resolution submitted to the First Committee on the report of the Conference on Disarmament (L.14), which the General Assembly subsequently adopted without a vote as resolution 79/71.

Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters

The Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters held its eighty-first session from 31 January to 2 February in Geneva and its eighty-second session from 26 to 28 June at United Nations Headquarters. Shorna-Kay Richards (Jamaica) presided as Chair of both sessions.

The Board began a two-year programme of work focused on international peace and security risks emanating from advances in science and technology. It undertook a strategic foresight exercise aimed at identifying emerging peace and security trends; exploring interactions between technology and weapon systems; assessing impacts and governance mechanisms; and proposing measures to address risks and opportunities.

In its progress report to the Secretary-General (A/79/240), the Board outlined its preliminary considerations, informed by discussions among members and with external experts. The body was scheduled to issue formal recommendations following its eighty-fourth session in June 2025.

Over the course of its deliberations, the Board emphasized the dual potential of scientific and technological developments to either support disarmament, development, peacebuilding and human rights protection, or exacerbate inequalities and conflict dynamics. In this context, the Board noted a growing need within the United Nations for a systematic analysis of how scientific and technological advancements intersect with issues of disarmament and arms control. Key concerns included ensuring human control over AI and autonomous weapons; adherence to international law; understanding the roles of States as well as non-State actors, including the private sector, civil society, the scientific community and non-State armed groups; and examining how technological advancements interact with existing weapons, particularly nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction.

Turning to potential policy approaches, the Board recognized that effective management of technological impacts requires proactive and coordinated efforts at the national, regional and international levels. It emphasized the pivotal role of the United Nations in fostering international cooperation, establishing norms and setting global standards in the evolving landscape. Board members discussed establishing standardized terms and criteria for evaluating peace and security risks of various technologies, such as a matrix to help to determine whether technologies should be monitored, regulated or prohibited. The Board considered options for adapting existing multilateral frameworks, as well as regional and bilateral forums, to address technological advancements affecting nuclear arms and other weapons of mass destruction. Members also explored opportunities for conducting technology assessments, establishing new dialogue platforms, enhancing research capabilities and promoting public ownership of computing capacities through publicly funded initiatives.

In its capacity as the Board of Trustees of UNIDIR, the Board reviewed UNIDIR’s current programmes, activities and finances, including ongoing efforts to strengthen policy impact, achieve financial sustainability and further expand global engagement. The Board was briefed on UNIDIR workstreams addressing AI implications for international peace and security, as well as new developments in space security. In addition, UNIDIR provided information on the objectives and planned activities for its Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction-Free Zone Project. Trustees discussed recent UNIDIR activities, including Security Council briefings on cybersecurity and small arms, capacity-building initiatives in AI ethics and international law, and improvements to strategic and global communications.

The Board endorsed plans for UNIDIR’s programme of work and budget for 2025, emphasizing core research areas and the need for sustainable funding to support its vital research functions amid evolving global challenges.

Footnotes

-

[1]

Approved: Angola, Armenia, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Holy See, Jordan, Kuwait, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Libya, Niger, Panama, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Thailand and United Arab Emirates. Not approved: Albania, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Slovenia and State of Palestine.

↩ -

[2]

Only one woman had previously chaired the First Committee: Mona Juul, then Deputy Permanent Representative of Norway, who held the role in 2006.

↩ -

[3]

The General Assembly decided to convene the joint half-day panel discussion by its resolutions 78/52 and 78/72.

↩ -

[4]

Unlike the other Main Committees, the First Committee had maintained the practice of not revealing delegations requesting votes in view of the substance of the Committee’s work and its direct relationship to national security. In 2023, the delegation of Singapore pushed back against that practice, arguing it was not in line with the procedures of other committees of the General Assembly or with the principle of transparency. Singapore and South Africa jointly submitted the draft decision “Information on requests for votes” for adoption by the First Committee. The General Assembly adopted it on 2 December as decision 79/516.

↩ -

[5]

PAX, King’s College London, International Campaign to Ban Landmines, Cluster Munition Coalition, Access Now, University of Baltimore School of Law and Harvard Law School Project on Disability, International Network on Explosive Weapons, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Mines Action Canada, Human Rights Watch, Control Arms, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy, Project Ploughshares, International Action Network on Small Arms, Pace University, Open Nuclear Network, International Peace Bureau, Stop Killer Robots, Pan-African Reparation Initiative, and the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

↩ -

[6]

Australia (also on behalf of Canada and New Zealand), Austria, Cameroon, China, Cuba (also on behalf of Nicaragua and the Islamic Republic of Iran), Egypt, El Salvador, France, Hungary (on behalf of the European Union), India, Lithuania, Mexico, Nicaragua, Russian Federation, Singapore (also on behalf of South Africa), Slovenia, Switzerland, United States and Uruguay.

↩ -

[7]

The General Assembly adopted the text on 2 December as decision 79/516.

↩ -

[8]

Austria, China, Egypt, El Salvador, Germany, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Netherlands (Kingdom of the), Philippines, Russian Federation, Switzerland, United Kingdom (also on behalf of Albania, Australia, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, Netherlands (Kingdom of the), New Zealand, Norway, North Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Republic of Moldova, Romania, San Marino, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Türkiye, Ukraine and United States) and United States.

↩ -

[9]

International Committee of the Red Cross.

↩ -

[10]

Algeria, Angola (on behalf of the Group of African States), Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Cambodia, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, El Salvador, France, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia (first on behalf of the Non-Aligned Movement and subsequently in its national capacity), Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati (also on behalf of Kazakhstan), Lao People’s Democratic Republic (on behalf of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations), Latvia (on behalf of the Baltic States), Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Paraguay, Philippines, Poland, Qatar (on behalf of the Gulf Cooperation Council), Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia (first on behalf of the Group of Arab States and subsequently in its national capacity), Sierra Leone, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Switzerland, Syrian Arab Republic, Thailand, Tunisia, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United Republic of Tanzania, United States, Uruguay, Viet Nam, Zimbabwe, Holy See, State of Palestine, League of Arab States and European Union.

↩ -

[11]

Those presentations were provided by Jimena Viveros of the High-Level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence; Sarah Grand-Clément of UNIDIR; Elina Noor of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Pavel Karasev of the National Association for International Information Security; James Revill of UNIDIR; Peter Hotchkiss of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons; Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan of the Observer Research Foundation; Timothy Wright of the International Institute for Strategic Studies; Thomas Withington of the Royal United Services Institute; and Frank Grosspietsch of the United Nations Regional Centre for Peace, Disarmament and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean.

↩